by Leslie Leonelli, exclusive for The diagonales

I was 5 years old in 1950 and my grandfather, a doctor and socialist, used to say “We’ll be invaded by yellows”, understood as Chinese. I saw the prophecy come true in my house.

If a fortune-teller had told me this, I wouldn’t have believed it, but Paola Min, a 60-year-old Chinese friend, considered a sister, who has her own house and sometimes comes with her dog Pasquà, when she doesn’t feel like sleeping alone, often sleeps in my studio. Unfortunately I have a black cat whdiagonals.ito intends to maul the dogs, so the canetto must be sheltered. Paola Min was born in 56, perhaps the first Chinese born in Rome, to a couple of former rich Cantonese opera singers, who were prevented from returning to China by the arrival of the revolution. Musician, actress, clown, artist, art-therapist, Paola Min also teaches Thai Chi and Chi Kung to FAO employees and that’s how she maintains herself. And this is perhaps the first Chinese, with strong Romanesque inflections, that I met in 1990.

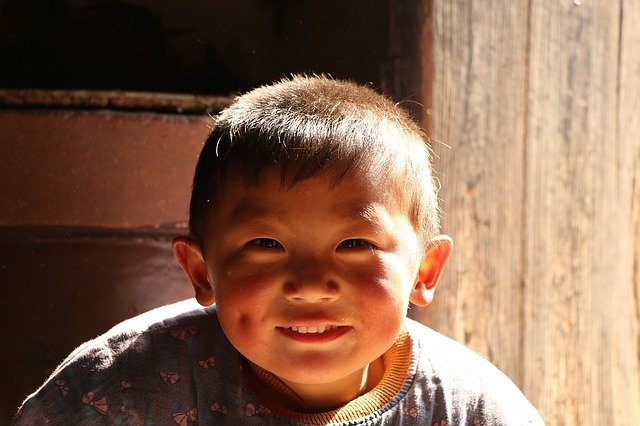

In another room sleeps Jo Lan, a Tibetan-Chinese who studies as a soprano at the Conservatory of Santa Cecilia whose traditional sexual costumes are far from those of the bigoted Chinese, whether they are Buddhist or not. And then in the smallest room, Aina Shi, the girl who calls me Grandma.

Since about 1996 I’ve been having my clothes repaired by a very fast Chinese woman named Lin Li, by now Lilli for everyone, in Via dell’Acqua Bulicante, a former suburb between Casilina and Prenestina, where Pasolini used to go to pick up his street kids, with still some old heroin dealer in danger of extinction and some retired whore, but now a multi-ethnic neighborhood and also a bit of fashion, since we are just a little bit further than Pigneto.

Until 2008 Lilli had a shop without a door, open air, like the shops of Ostia Antica, only the shutter, and her daughter Aina, a very young girl, played on the sidewalk under her control. When Aina was 5 years old, Lilli was convinced by a choir of fellow citizens that Chinese schools were more serious than Italian schools where they just play, so in 2001 he took her to Wenzhou to her mother. But the little girl was lively and busy and her grandmother was too busy to look after her, so she passed her on to a sister, but she always played mahjong and often forgot her presence. Then, with time, they discovered that Aina was born in Italy, she wasn’t Chinese, nor Italian, so she had to pay 450,000 lire per month for school, so after 8 months her mother took her back to Rome. But the little girl had changed, bent like a clubbed dog, and so she stayed. But every now and then Lilli would let me take her away, to me without children and hungry for childhood, maybe for a day at the beach, because nobody ever took her out, not even for a lollipop, not even on Sundays, just home, shop and school.

Lilli and her husband Giuvè live in a nice apartment (if it were restored) with three bedrooms and bathrooms, on the fifth floor, bright and without elevator (amen, the movement is healthy), except that it is without heating and without windows in the kitchen and bathroom “That way it always gets air in the house and does not smell like the others”. I spend the winter there, but I don’t accept invitations to eat there I call it “Colosseum”. Giuvè was a cook for many years and in China his bed was the kitchen table, in Italy he was a chauffeur for the Chinese, but now he doesn’t work anymore because he is prematurely worn out.

Lilli keeps the apartment always very clean and has become the owner, together with her husband. She borrowed some money from her mother in China, then Lilli rented 2 rooms, each one to a Chinese family, 2 or 3, or 4 per room, and besides doing repairs in her shop, she cleaned and cooked for everyone. The TV on non-stop in overly sophisticated Chinese, which Aina understood little or nothing about.

When Aina turned 12, LinLi finished paying for the house, sent the guests away and took possession of the other two rooms and moved her work home.

Ever since I’ve known her, Aina has been drawing. All she needs is a blank sheet of paper and she fills it with drawings that are now very refined, before comics, like when they stole my backpack that I, like every morning at that time, did Tai Chi in a group in the garden of Piazza Vittorio, and Aina told it inside her squares, including about a thief who ran away with a black mask like that of the Dachshunds gang.

Aina, who now surprises her teachers at the Art Academy, is always drawing, drawing is her paradise, her refuge, and already, according to her middle school professors, she was overwhelmed and the teachers have indicated the art high school as her vocation destination. I added to her parents that other choices would make her life miserable. LinLi didn’t want to, but I was at their house the day they had to decide, she understood and agreed immediately.

Giuvè, born in 1959, lives in fear that the money will run out, that there will be no food. Giuvè’s older brother, the favorite, handsome and smart and proud, died of hardship.

After the famine of World War II, between 59 and 61, an epochal famine in China struck the entire country, from Siberia to the tropical South. In just three years, 30 to 60 million people starved to death. A catastrophe of that magnitude had never been seen before. The trees were flayed, the leaves ripped off, cats, dogs, cockroaches, mice… to the point that some families exchanged their children with their neighbours to eat them. The cannibalism in the campaign was such that all the people interviewed claimed to have witnessed these episodes. Some were shot for cannibalism, others committed suicide out of guilt.

We in the West in the meantime have only heard rumours that have not been taken into account, and even in China in the third millennium it carefully removes what happened. It is simply forbidden to talk about it.

This past, of which we have no similar memories in Europe, explains the drives to work tirelessly and to become rich for many Chinese today. The hunger is from yesterday, not centuries ago. Taxes are not high, but health care is not free and those without money risk non-assistance.

In the ’40s, in the countryside, Giuvè’s mother had been married at the age of 5 and he, who came from a family a little more affluent because he was an umbrella maker, was 8 years old. Her parents were anxious to get rid of a mouth to feed and these two children, 10 her and 13 him, had gone into town, on foot, looking for work.

Of all those born, only 5 were recorded: two females and three males. All the others abandoned or sold or who knows?

Giuvè until he was 55 years old, he earned about 1000 € per month, and he gave everything to Lilli, keeping less than 50 € that every month he kept for himself, using even less, but in the pockets of his trousers he kept at least 3.000 €.

He wants to have protection from the fear of suffering those hunger bites he can’t forget.

He doesn’t want to know about China, while Lilli would just like to return to her family of origin, which currently lives comfortably, with air conditioning and even a second home in the country.

By the time she was 15, Aina’s teeth were all crooked and jammed in, making her look like a toothless old lady. There was no question of spending on braces (after all, money could get them out in the end). It made an impression on me and I couldn’t stand it – now, or never again – in September 2011 I decided to take her to a university centre for braces and finance it myself.

A few months later, when Lilli heard about my broken leg in Chiang Mai, Thailand on January 3, 2012, she told me on Skype: “You took care of us and now we take care of you.

Back on crutches and with little autonomy, Aina came to stay with me. She would go to art school in the morning, LinLi would come to cook, then after lunch she would go home and do her repairs.

When in February the snow fell on Rome, certainly not equipped and all public transport interrupted, Lilli arrived walking for about 4 km. On the other hand, these Chinese are the children of the “long march”. Although sometimes I find their superiority complex unbearable.

After 2 months Aina begged me to stay here and live. Which was also approved by the Chinese maternal grandmother who runs the whole thing and decreed “You can’t give her what she offers”.

But there began the problems of belonging: “You sold your daughter to an Italian”, while on the Italian side began the suspicions “You’re an old woman who’s being circulated by the Chinese who want your money”. But while my Italic side was kept under control by me, the Chinese fear of “losing face” was unmanageable and during these years Aina often couldn’t resist, returning to live at her parents’ house through doors slammed with anger.

Then she came back even after months of absence. In fact, not only did he feel suffocated at home, but he needed school assistance because of the Italian language and different worldviews.

Teachers are deceived because the Italian spoken by immigrant children is without strange accents, the little Chinese children are very good at pronouncing the erre, indeed they also acquire dialectal inflections and all automatically take the role of interpreters for their parents. Aina passed her final exam with difficulty in primary school. Treated like a fool by some teachers, when she was 10 years old she thought she’d jump out the window. In fact, like so many, she felt like she was in an aquarium not understanding what they were telling her. In the morning in Italy, in the afternoon and in the evening in China (but he didn’t understand Chinese TV either) only the narrow family vocabulary of semi-illiterate parents.

How did he survive so many years? Learning by heart from books and notes. But you know that with time studies become more complex and difficult. So after the door slammed, he often felt the instrumental need to come back to me and also have intellectual stimuli from me and my friends.

It was with pleasure that I studied many subjects with her, on texts that I found updated with respect to my times, such as studying the Crusades with all the deceptions told to us, and also the school cultural stalemate with the absurdity of a history that almost does not mention the 30-year war in the centre of Europe, nor Chinese history or the history of other nations other than Italy, England or France. How can you explain the exoduses and migrations?

The professors with whom I spoke about Aina’s difficulties understood, also because nobody explains to them that the language is such an obstacle for the second generation Chinese that, despite their superior ability to concentrate (the Chinese never interrupt their children who are studying) and the widespread economic possibilities, they manage to get to university in very few.

To look for some company Lilli, she decided to attend the Evangelical Chinese Church, which has a large headquarters in Esquilino, and Lilli goes there to have some socializing and to sing (which is her passion). It’s forbidden for girls to wear make-up, priests are married but very retrograde. The threat of dying and suffering the fires of hell is very present. But Sunday lunches and Friday dinner are free for everyone because they are offered by the community, financed mainly by a rich merchant in search of good health and paradise.

Prayers are made aloud, so it was easy for Aina to grasp “Let me have lots of customers” or “Let me earn lots of money, O Lord”.

Then outside there are the conciliaboli in which they talk about Italians: “certainly: Italians are nicer, but lazy, slow, lazy and always want to be on holiday”.

The Chinese are convinced that their schools are unbeatable, and this is how their children often do it and then send them to China, but being born in Italy they are stateless until the age of 18. In fact, Chinese schools are very tough. The language with all the thousands of ideograms is language for the rich, implying a very long time, not as we have only 26 letters to combine in the end. But then in meetings at the university they find it difficult to express their opinions.

Many Chinese make their children in Italy, then at the age of 40 days from birth, they give them to their parents in China and then take them back at the age of six, when they can entrust them to Italian schools. Sometimes they return to Italy as teenagers to support their parents in the shops. Attachment problems and detachment trauma are not taken into account. Almost all children are aware that they have been conceived for a purpose: to support their parents in their old age. This explains the rigid and anaffective attitude, the facial expression that Aina and I now call “stone face” that makes them socially unpleasant and immersed in the feeling of indifference, and also, as we whisper in the community, the high suicide rate among adolescents. Which of course is whispered and hidden “so as not to lose face”.

Marriages are mostly arranged by parents, but in order not to “lose face”, they remain united in mutual unhappiness.

Ligia to tradition, Lilli tried to combine engagements to Aina, but helped by her strong artistic vocation, she made time to meet Italians and Chinese bourgeois at the Academy of Art, to excel in engraving. and to convince herself that marriage can wait.

Then we’ll see.