Born of French parents in Zimbabwe, Claude Jammet grew up in Kenya, India and Japan, in addition to extended periods in France, before settling in South Africa where she began her career first as an illustrator in an advertising agency, then two years later, after her first solo exhibition, as a professional painter. Love made her move to Italy more than two decades ago, where she now lives and works in a small Ligurian village.

She describes herself as a self-taught artist, although she decided to be a painter when she was only four years old and, since then, never stopped designing and painting, with the warm support of her parents, looking with passion at all the books she could find on painting and the great masters.

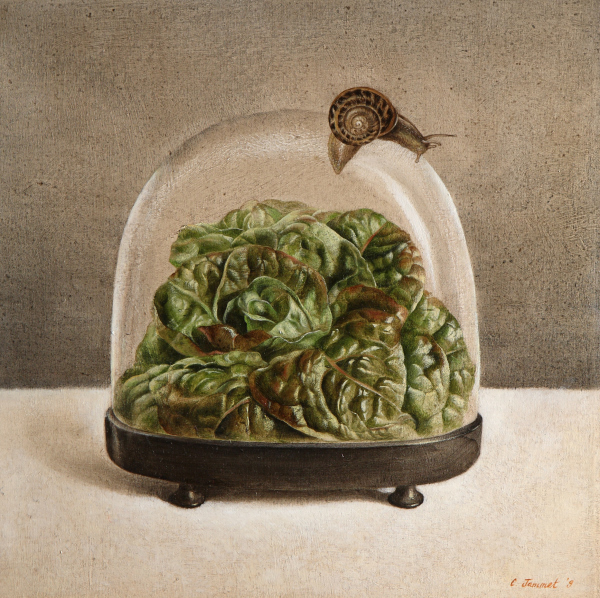

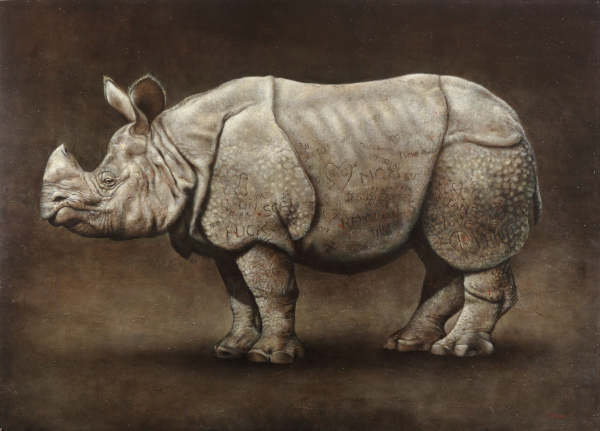

Painting for her is not only a vital requirement but it is also a way to communicate her experience of the many different worlds and cultures that she has lived, and which forged her personality. It is a way to communicate her vision of world evolution, of human impact on nature and on mankind itself. Although her work refers to the perfection of nature and man, it is often a cry against its destructive nature and on the wrong way mankind dominates nature for his own interests. Therefore, many, but not all, of her paintings are a kind of recollection of species at risk of extinction or, symbolically, illustrate the void created by their disappearance to the point of entitling one of her exhibitions “Anthropocene”. Even the apparent distress they create facing the mess we have made of Mother Nature, those paintings never miss a point of exquisite humor introducing unexpected details of modern consumer society.

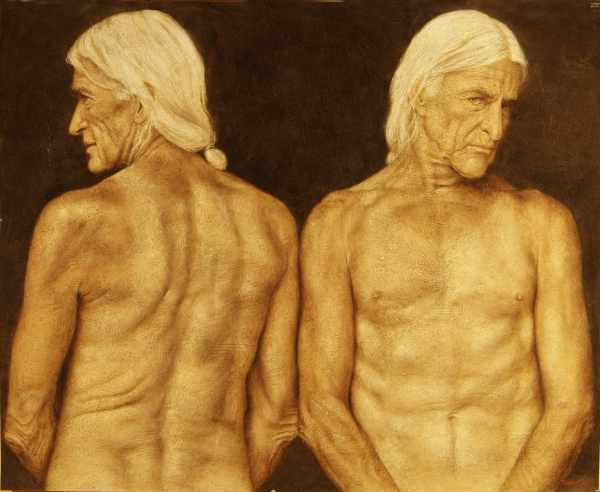

Being a realist painter, sometimes bordering on Hyperrealism, often details or backgrounds are painted in an expressionist or abstract manner. She likes to play with reminiscences of the old masters demonstrating her profound knowledge of the history of art with which she plays in a very natural way with elegance, “en passant”. In the same way, she is fascinated by rituals, specifically religious ones, realizing works (exhibited under the title of “Cultus”) that display that without irony, but once again not without a certain humor and tenderness, as if past human behavior and beliefs were creating a form of nostalgia for cultures which are disappearing.

Over a career spanning more than four decades, she has held many solo and group exhibitions in South Africa, Europe and Japan. She is represented by several galleries in South Africa and, in London, by the Everard Read Gallery where she is presently participating in a group exhibition entitled “Against Interpretation” and is now preparing a solo exhibition in 2021. She has received several international awards, the last one being the gold medal for the Turio-Copello Prize in 2019.

Her work can be found in numerous private and corporate collections in South Africa and across Europe.

Claude Jammet

Interview by Thierry Vissol

Thierry Vissol: You claim to be a self-taught artist, although you have been painting since the age of four and have studied all your life the history of art, the techniques of the old masters, and analyzed the content of their work. Isn’t that what is usually taught in art schools? And why did you refuse to frequent one?

Claude Jammet: When I declared at age four that I was going to be a painter, I could not read, let alone study the history of art or technique. The impact Art had on me as a very young child was to give me drive.

At school I took Art as a subject, but I did not have good grades because I never followed instructions. So, when I finished school, and my parents offered an art education, and given my school experience, I turned down the offer. Instead I proceeded to teach myself by looking at a lot of art, reading, analyzing, and of course practice. I suppose I arrived at the same result, but on my own. I don’t think one can presume to teach someone to become an artist. In time, history decides that.

Thierry Vissol: You held your first solo exhibition at a very young age, which convinced you to quit your job and to dedicate your professional life to painting. Do you think that painting is a kind of destiny inscribed in the genes of painters? Or is it a more psychological approach to both realize yourself and protect you from the real-world aggressions?

Claude Jammet: The job in question was illustration for an advertising agency. Quitting was easy because the two years I spent there were restricting to say the least. I was just a machine pandering to the clients’ every whim. I had to use a projector and photographic reference to “save time and make money”. At least I learned what I did not want. Leaving the job was a leap of faith, and I did not know how I would survive or “if” I would survive. I guess that the four-year old’s notion paid off in the end!

Thierry Vissol: You lived in many countries with a wild nature, like Kenya or South Africa where you still seem fascinated by the desert and beautifully impressive immensity of the Karoo. Is it this proximity, near communion, with nature, that awaked your interest in endangered species, like the black rhino or the riverine rabbit, and motivated you to portray them in such a “human” way?

Claude Jammet: In my case, it happened the other way round. The first subjects I painted at age four were the animals I saw in Kenya where I lived. Later I chose to live in wild, remote places where I could be in harmony with nature and where those creatures were not in danger.

I hope I portray these wonderful beings in a “humane” rather than human way.

Thierry Vissol: There is a kind of activism in your paintings against the devastating consequences of human activities and consumer societies (Anthropocene). You therefore introduce winks (clins d’oeil) like a bar-code on a zebra or graffiti on a rhino hide. Do you think that an artist has, in his art, a role to play in political debates?

Claude Jammet: If I have any role to play, I doubt that it is political. Perhaps it is ethical? If I can sensitize just one viewer to the plight of species, I have done my job.

Thierry Vissol: In many paintings you represent old objects or skulls, empty nests, giving at the same time a sense of timelessness and of life’s fragility. Is it an influence in the “vanitas” tradition?

Claude Jammet: I think the motivation is in the transient nature of all things – which saddens me. The Vanitas still life language of the past is limited.

Thierry Vissol: Remaining on the subject of your influences, you seem to be like a sponge, absorbing and re-elaborating multiple influences. Nevertheless, I felt in your still-life work a similar sensation of plenitude as when reflecting on the Giorgio Morandi still-lifes. As he does in his work, your objects, still-lifes or portraits have complex neutral backgrounds. Why so?

Claude Jammet: To give centre-stage to the actual subject/object by excluding anything that might distract from it. It does not mean that interesting things can’t be happening in that space, like scratches, marks or nuances of colour.

Thierry Vissol: Although you perfectly master perspective, your paintings get strong dynamism thanks to your capacity to elaborate details, a technique used by Jean van Eyck and many Flemish painters before they decided to adopt the Italian Renaissance way of painting. Why so?

Claude Jammet: The illusion of perspective and space around the subject does not need architecture or nature to define it. Tiny things like stones or twigs and their shadows achieve that without distracting from the subject.

Thierry Vissol: Another of your fascinations, very much linked to your vision of history, personal or general, and perhaps to mankind’s present apparent regression, is for rituals, religious or other. Why so?

Claude Jammet: Ritual elevates the mundane to a holy level. Think of the Tea Ceremony. All worthwhile things require time – something we seem to lack more and more. Nowadays we pop a teabag into a mug and drink that while doing business on the phone.

Thierry Vissol: You are mostly a realist, sometimes even a hyperrealist, painter. Another painter, mostly abstract, that I interviewed was affirming that “Even great realism – while impressive in its display of acquired skill – tells the viewer everything within moments – and you stop looking”. But you participated in an exhibition entitled “Against interpretation”. Would you agree with Susan Sontag that the will to interpret a piece of art, specifically if realist, detracts, or reduces the power of art and that in the contemplation of a piece of art we need to take time and recover our senses: hear more, feel more and see more?

Claude Jammet: I am a realist painter, but I refute the title of Hyperrealism. It may seem as if I paint every hair or every blade of grass, when in fact it is one small detail which makes the eye of the viewer fill in the rest. As for great realism boring the viewer within moments, I could look at Velasquez’s “Las Meninas” every day for the rest of my life and rediscover it endlessly.

I couldn’t agree more with Ms. Sontag because to interpret also means to “box” or label – a habit we can’t seem to do without.

Thierry Vissol: What do you think of abstract painting?

Claude Jammet: A lot of bad work has been passed off under the label of Abstract Art. All art is abstract – if you can recognize a painter’s style, then the painter has abstracted reality. Chaim Soutine is not an abstract painter, nor is he a realist, he is just great! And, let’s face it, not everyone is a Rothko or an Auerbach!

Thierry Vissol: You sometimes paint nudes, mostly women? What do nudes represent for you?

Claude Jammet: I have actually painted more male nudes. Men are less self-conscious for their little defects whether dressed or naked. In portraiture the body is as telling as a face, and the little imperfections make for personality. Some years ago, I painted a friend who had severe burns on half of his body. When I asked him to sit for me, he wanted to know why I chose to paint his scar. He was only two years old when the incident had occurred, and it is said that “…scars are the place where the soul tried to leave the body and has not been able to, where it has been shut in”. He seemed very pleased with my explanation.

Thierry Vissol: In an interview you said that art was the only religion for you. What do you mean and what is and what is not art for you?

Claude Jammet: To be on receiving end of true art (whether music, literature, dance, film etc…) is akin to a mystical experience. Years ago, I was lucky enough to see the big Francis Bacon retrospective at Beaubourg in Paris. I went around exhibition three times in an attempt to imprint what I knew would be a life altering experience. Only real art achieves that, the rest is posturing.