Though originally hailing from Upstate New York, David moved to Colorado at a young age where he spent half of his life. He has spent the other half residing in Europe. He lived for a while in France and Belgium, as well as Japan, during an extended travel throughout Asia in the 1980s. He has since settled in Copenhagen, where he currently lives and works.

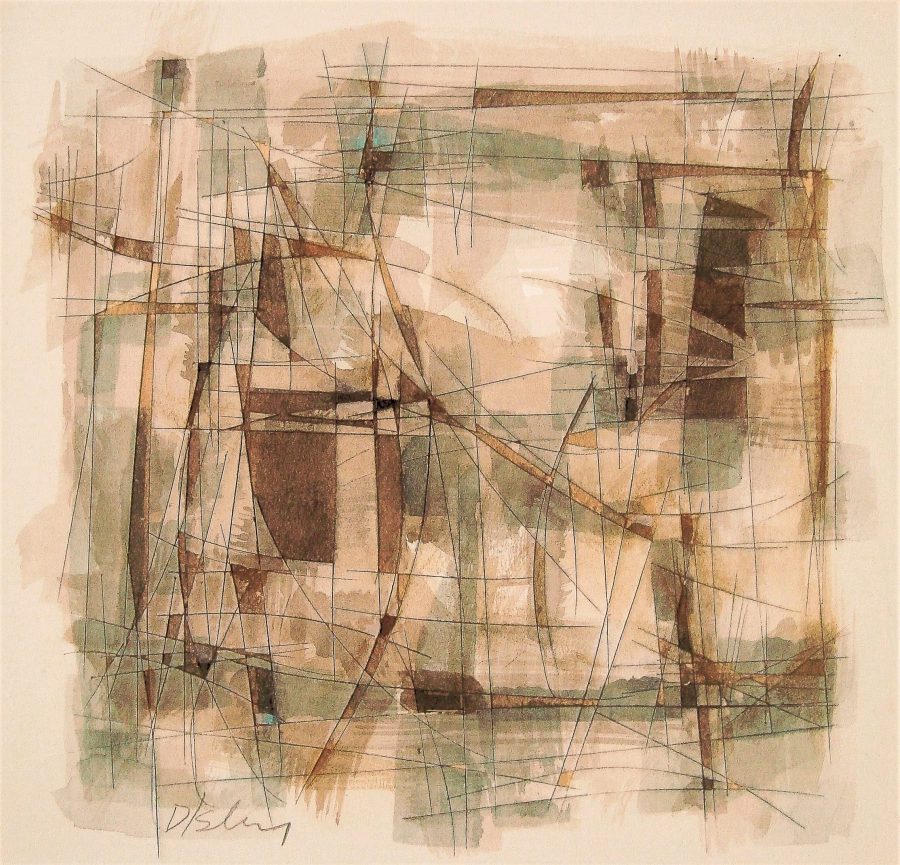

At age 17, David ran a figure drawing class at the University of Denver while beginning to exhibit his work with success. Attending Pratt Institute in NYC, he majored in printmaking while taking further classes at Columbia University and The Art Students League. Back in Colorado, he worked as an assistant art dealer. After being offered a position at The Colorado Institute of Art, he taught drawing for a number of years while continuing to exhibit his work throughout the US and internationally.

Having been included in several international graphic arts and photography annuals produced by the ICO (International Creator’s Organization, a Japan based Company), David was asked to head its Denver Bureau.

In Copenhagen, he has had a long association with FOF (Folk Oplysnings Forbund, an organization promoting life-long learning) where he teaches an innovative free expression course entitled “David’s Class”. He has also held creative drawing classes at Copenhagen’s Glyptotek Museum. During the summers he holds private outdoor drawing and painting sessions around the city.

As of late he held an art and design lecture at Copenhagen’s Rundetaarn (The Round Tower), followed by a weeklong workshop and month-long exhibition. David was recently hired as artistic supervisor for the development of a piece of artwork featured in an independent documentary film (“Epidemiens Ekko”), broadcast on DR2 (Danish TV), June 23, 2020.

Otherwise, he continues his own art, most of which is sold and sits in private and public collections throughout the world. He has had numerous solo exhibitions internationally, including museums such as Tokyo-To Museum of Art in Japan, or at the Centre Culturel Jean Gagnant in Limoges (France).

He has received numerous accolades and awards for his art and teaching work. As a young teenager he won 1st place (mixed media) in a National Scholastics Contest held among tens of thousands of schools across the US. A decade later, the American arts magazine, Artists of the Rockies, did a feature article on him. Later, at a 10-year retrospective exhibition held by the magazine, he won 1st place. At Tokyo-To Museum, while exhibiting with the Shin Yoga Kai (New Wave), he received the top award (Chairman’s Prize). He has received the only Teacher of the Year award endowed to date by FOF, from among 736 teachers nationwide.

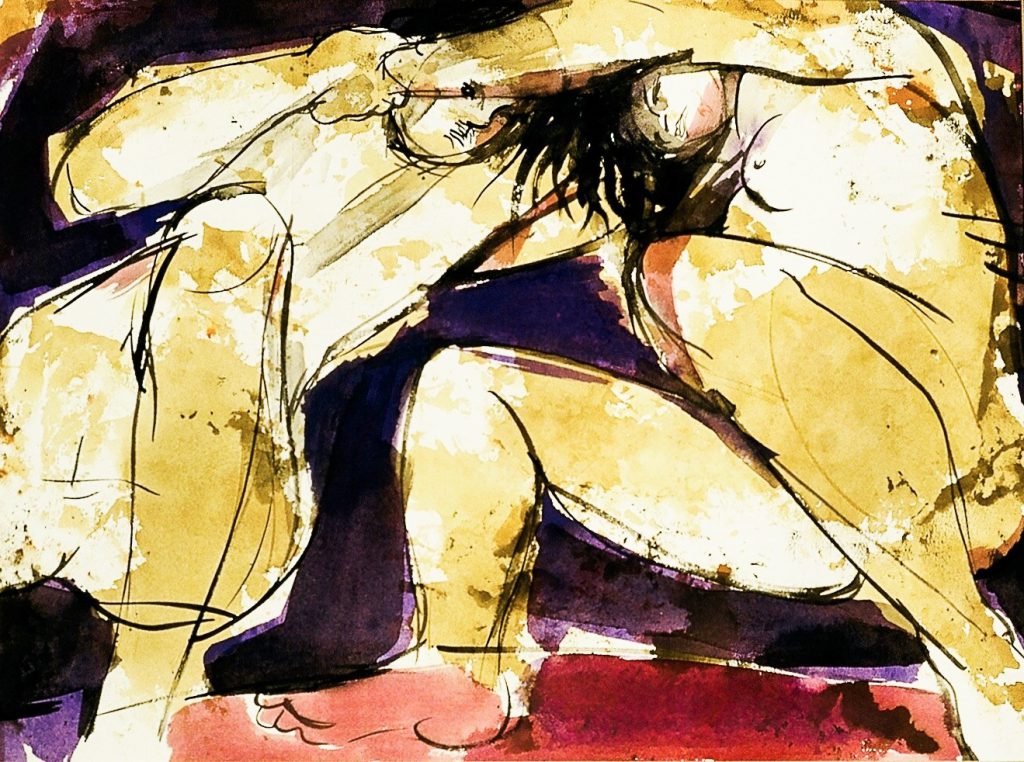

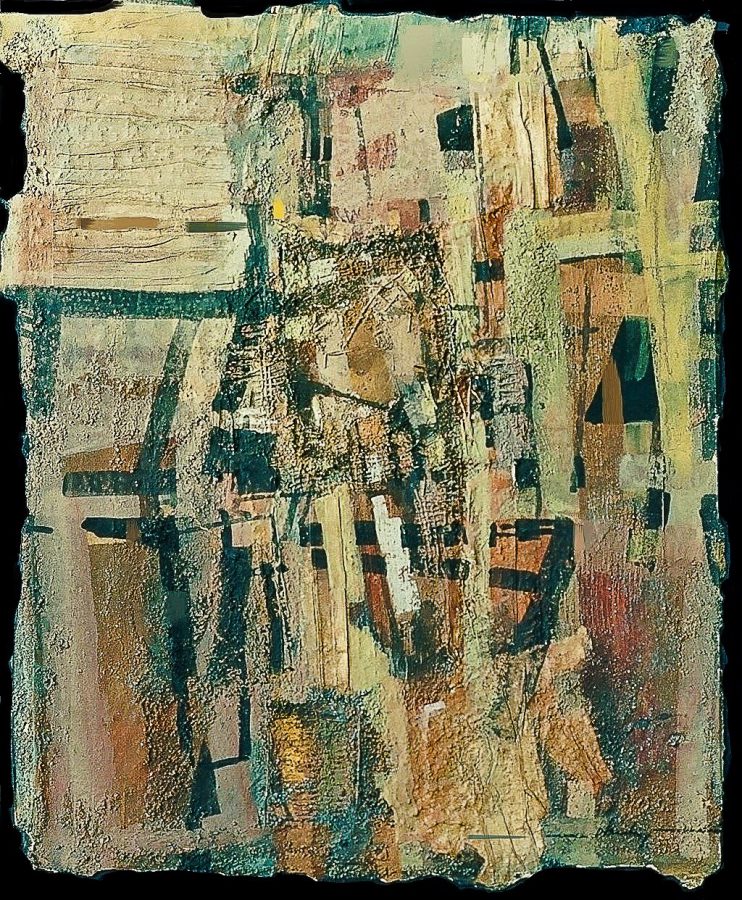

Art on the cover: Couple (gouache, paper), Private collection

David Isenberg Interview by Thierry Vissol

ThV – You have been quite a precocious and famous artist, earning your way and travelling about the world, thanks to sales of your paintings. How did this happen?

DI – Well… thank you for the label of “famous”, but that’s strictly debatable. I’ve been fortunate.

ThV – You do not like to speak about yourself much, contending that your art should speak for itself. But people like to know about the person behind the scenes. Could you say a word about your passion for painting? What is your artistic quest?

DI – Being an artist is something you live and breathe. It could never be a mere hobby for me. There is no quest, per se, but to continually move forward in the work. It is something relentlessly but enjoyably pursued. An artist develops a personal aesthetic, which is examined, prodded, engaged, and furthered. We move ever onward, for to remain static (which is often commercially viable) is to arrest the process. Some artists have a form of work which they repeat endlessly, while other artists have “best periods”. Others develop inexorably throughout life. I would like to be one of the latter. I desire to make art that is continually compelling, that one never tires of looking at, even after discovering every minute detail numerous times. If I manage that then it has been a successful day for me.

ThV – Although you are primarily a painter, you say that drawing is at the heart of your work. Why so?

DI – Armenian-American artist Arshile Gorky was very succinct on this: “Drawing is the basis of art. A bad painter cannot draw. But one who draws well can always paint”. They are two vastly different disciplines for me but interconnected. I do not paint from my drawings. Drawing is an art unto itself, not in service to painting. Painting requires a broader skill set but having a well-honed eye and hand never hurts and nuance is everything. Drawing provides all of that: developing perception and precision.

In its own right, it is an immensely powerful art form. It possesses many levels of skill, the very least of which is precise depiction. Every artist should master this, but every artist also has a form of handwriting when they draw – an extension of their personality. How they go about the task ultimately changes the image and expression in every way. Speed can be a great friend when drawing but a difficult friend at times. It generally requires a high level of confidence or a low level of impatience.

ThV – Another process you are very fond of – and practice regularly – is printmaking. Is it just a pleasurable activity or does it have an influence on your style of painting?

DI – Both. Something in my disposition is drawn to the unique process of printmaking, the “Aha!” moment when your print is finally revealed – be it the final result or just a step along the way. It’s a moment of surprise – and who doesn’t like surprises? While printmaking often involves the production of identical multiples, the inherent aspect of playful creativity within the medium has always held much greater interest for me. Monoprints have tremendous appeal, while each print becomes a one-of-a-kind work of art.

Printmaking is a highly work intensive process at heart, and perhaps this has had an impact upon how I paint – not so much in terms of my “style” but in the approach to how I go about it. Or maybe it all just comes from the same place. One thing I never do is simply paint directly upon canvas. More often than not I will employ a work-intensive method with a variety of preparatory steps. Yet something as simple as a rapid sketch with a few added bits of collaged paper can get right to the heart of a universal vision (see: Red Train).

ThV – In your paintings you very often employ a wide variety of media as well as mixed textural elements and use an assortment of tools other than brushes. Why?

DI – All media have interest for me and I have used them all, sometimes combined in certain pieces. Working with each requires a specific disposition.

I have a large appetite for texture. It adds an extra tactile dimension to the work, playing as great a role as form and color. I build up or carve away textures, employ collage elements, and sometimes print upon the surface as part of the overall effect. I commonly use knives, combs, rollers, sticks and even cardboard tubes, as well as brushes. In the end, the painting itself must be an object of beauty. The addition of texture contributes.

Recently I’ve been painting watercolors upon carved boards. Doing so creates a decisively enhanced challenge to an already difficult medium, but the results add a whole new level of visual interest. Sometimes I’ve applied lead paint to the images, followed by a patina which rusts the lead so that the rust itself becomes an element in the final result.

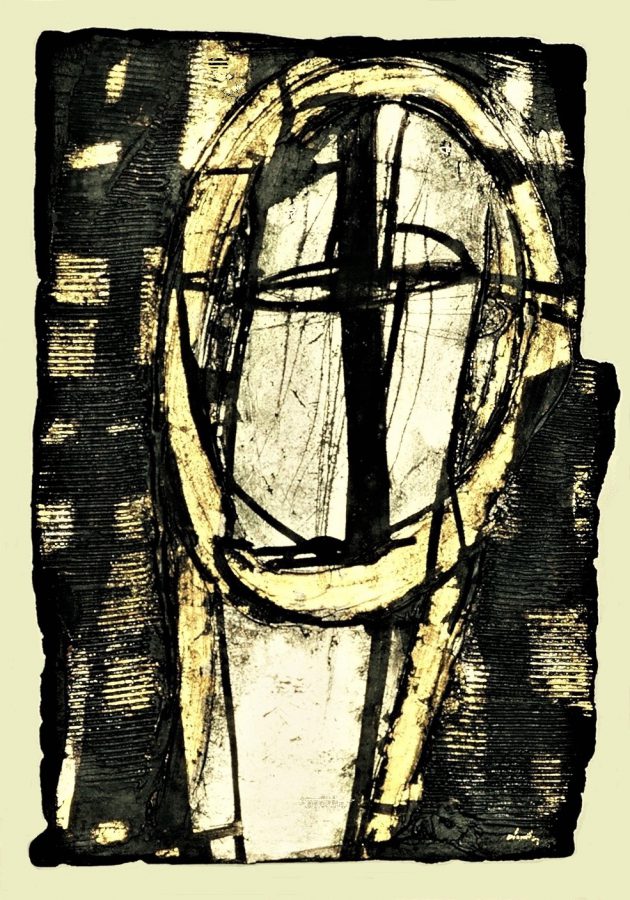

Another time I created a body of vaguely pseudo-religious looking images, which I came to entitle “Shrine Objects”. Textures were built up upon heavy boards by adding cloth, acrylic paste applied with knives and combs, then scratched, carved and covered with gold, silver, and bronze metal leaf. Next came a thin layer of oil paint and finally a “dirty” patina making them look centuries old and dragged up out of the earth. The largest was meters tall, encased in a hand-built plastic box. The smallest could sit on a bookshelf. Meant to appear mysterious, framing the objects was an intrinsic part of the final effect. They were floated 1-2 centimeters off a linen covered surface and encased in very deep frames fronted by non-reflective glass, producing the subliminal effect of museum objects. Everything played a role in the finished result.

ThV – You say that “creating art is fun… and fun is about playing” what do you mean?

DI – I enjoy playing with materials, with my tools, with imagery. Fun and play go hand-in-hand. We hear the word play and we think of children, who would play all day if allowed to. Like children, we learn by playing and as with children, it taps into the internal life of an artist. And therein lies the true art: an unconscious extension of the individual.

Imagery becomes evocative. I could draw or paint a house… or a couple of leaves. If I only observe and depict the images precisely, what do I get beyond the merely recognizable? But how I play with an image can suffuse it with any number of qualities. The house may become spooky. The leaves, merely by how I juxtapose the forms and modify their sizes, color, their positioning in space, make the edges harder or softer, suddenly metamorphose into an undeniable message of human love. Wow! Is that ever fun to do!

ThV – You celebrate “free creation”, advocate “free and experimental creative activity” and teach a course of “free expression”; what does that mean concretely?

DI – Perhaps you are focusing upon the word “free”. It needs to be understood within context. By nature, I am a pluralist, preferring unencumbered creativity to remaining static within a single mode of expression. Doing the same sort of painting over and over is easy but it would quickly bore me.

I have a credo of sorts when I work. I refer to it as employing “controlled accidents”, which is achieved only when the artist relinquishes complete control as he works.

When I teach, I encourage my students to be themselves and to proceed in their own work as they like. I never give “how-to” lessons. I don’t wish to create an army of “little Davids”. They do things their way and I simply help them to be as good as possible at it. I believe in experimentation, whether you succeed or fail. The very nature of creativity embraces failure – and that’s OK. Creative people fail a lot and the good ones fail often… but like a phoenix we rise from the ashes of what didn’t work to a heightened sense of what does. No one gets it perfect all the time. No one is a god.

ThV – You mention “controlled accidents” in art. Could you elaborate on that?

DI – Some people may assume that an artist has a vision and then sets out to achieve it. I don’t do that. I never know – at any stage as I work – what the final endgame for a painting will be. If an artist follows – and sticks to – a pre-arranged plan and minutely controls every move, they are not working with controlled accidents, either in the details or in terms of the whole. This means about how the whole work turns out in the end. Letting go, allowing unexpected (even unintended) opportunities to arise and then engaging them is the process. The “accidents” which take place are always the best part of the work. They may change the outcome of the piece entirely. Alone they are nothing – just accidents – so they must ultimately be “controlled” with sensitivity, consummate skill and visual understanding. I can see in a heartbeat if an artist works under this premise – or not. Each artist will have their own unique way of doing so.

I had a friend – an excellent and very well-known semi-abstract artist in Germany. We occasionally painted together at his studio if I was in town. We weren’t very good at each other’s languages but the language of art was sufficient. He employed controlled accidents throughout his work, at every stage. We would occasionally argue – via hands and feet – whether such accidents could be specifically created or whether they had to appear – accidentally. Personally, I don’t think it matters when the ends justify the means.

ThV – You talk about helping your students to become “good”. What are your thoughts about good art and bad?

DI – It’s about skill and mastery, as much as such things can be discussed in certain work. Sometimes you just can’t – as with tribal art or earthworks. Generally, however, “bad” shows a lack of recognizable skill. “Good” shows understanding and usage. “Very good” is a display of finesse. “Excellent” is when the artist gets it perfect but makes it look easy, like child’s play. You cannot really determine these things without a comprehension of the skill set required.

Good and bad are not a subjective thing, which is about what you like. People often say “It’s good (because I like it)”. No. You just like it for whatever reason that you do. People like different things – and that’s fine. You can like whatever you want but it doesn’t mean the work is necessarily good. Not infrequently I see good art that I don’t like at all but I’ll never discount the fact that it is well done. Conversely, it can be difficult for me to enjoy poorly produced work, even if I appreciate where it’s going. If the final result is awkward and unsatisfactory, the good idea behind it is irrelevant.

ThV – Your work balances between recognizable images and abstraction. You consider yourself an expressionist. Could you explain this?

DI – I’m not really big on labels but they’re given to artists whether we like it or not. I define abstraction as a vehicle for translating reality, a way of transfiguring representation into something more. I very often employ recognizable images yet modified in some fashion. I have always done so. They may become imbued with whimsy, mystery or darkness. Contrary to what may be a popular misconception, working without images can be the greatest challenge of all. Being merely decorative is never enough.

Mark Rothko is a good example here. He did not personally subscribe to any art movement yet is considered to be an Abstract Expressionist. He painted blocks of color but they could be emotionally charged and quite precise with lovely, sensitive details. They might be evocative and meditative – or dark and contemplative as a gentle gong reverberating quietly in the stillness. Compare his work with that of Piet Mondrian, another giant in the art world. He also did blocks of color but devoid of human expression. That simply wasn’t his concern.

I have always aspired to people feeling, rather than merely seeing my work – and that probably makes me a latter-day Expressionist. It is me touching you in some way. Genuine feeling must come from within. We artists have materials, surface, form, color, line quality and a variety of techniques we can bring to bear but when the moment is right, some sort of magic happens. It is never conscious. It cannot be. The fact that I am even describing it in these terms defines my intensely expressive nature.

ThV – You are able to draw and paint absolutely realistically – but why do you disregard realism?

DI – Merely capturing an image with perfection has never held interest for me, although developing the skill to do so has. I can perfectly reproduce any image, yet I don’t find realism (mere copying) even remotely compelling. Even great realism – while impressive in its display of acquired skill – tells the viewer everything within moments – and you stop looking. Developing consummate skill is one thing but genuine artistry resides within the extension of the personality, the filter of the individual. Abstraction – by incorporating, synthesizing and translating images – becomes a vehicle to so much more than mere recognition or that particular display of skill and patience.

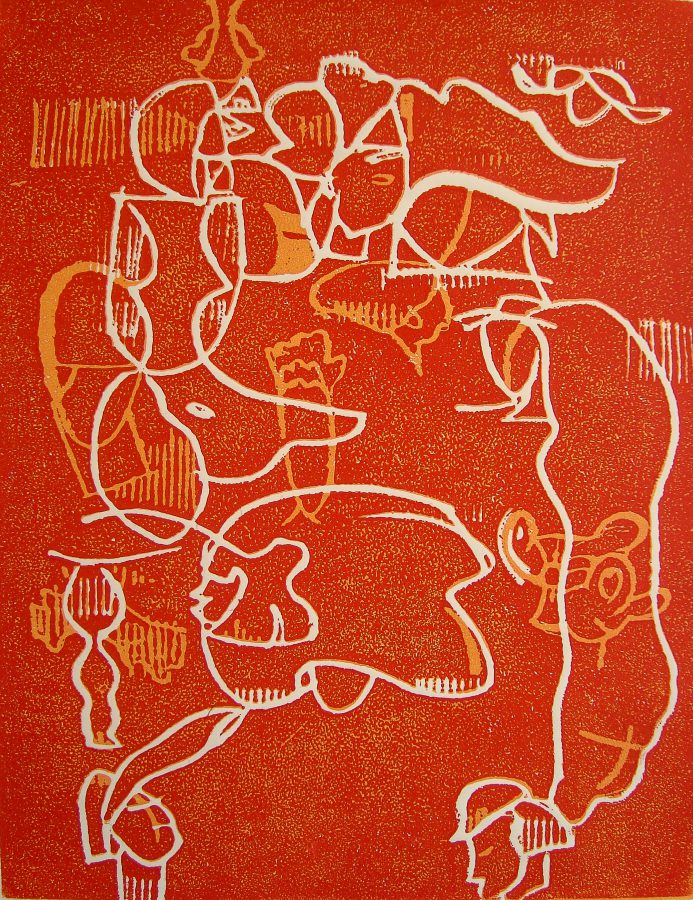

It is great fun creating highly evocative shapes that the viewer knows are heads, or birds or an army on the move – yet you haven’t actually painted those images whatsoever. I can be quite clear about it – or barely suggestive. Humor might play a role. From a distance a painting may look completely abstract and visually appealing in color, line and form – but up close the viewer begins to recognize whimsical 20th C. hairstyles (see: 20th Century Hair).

Realism may seem impressive to someone who has not developed the ability, but it is actually not that difficult to accomplish. Anyone can do it if they take the trouble and time to practice. It is simply a skill and all skills are learnable. Abstraction – good abstraction – is a whole other challenge, requiring a mindset, personality and a far broader range of ability. Anything poorly done is easy work. Bad realism is certainly easy… while bad abstract is the easiest thing to do. Good abstract is by far the hardest. One final remark: the best abstract artists are often excellent realists – but they have simply chosen another way.

ThV – Nevertheless, representation remains a starting point in your art. One of your watercolors is entitled “Bornholm” (a Danish Island off the coast of Sweden). Can you tell the story of this specific piece?

DI – I was together with a couple of my student/friends on a guy weekend of beer and painting. On one excursion we stopped for a break and to do a little painting. It so happened that the hillside we were on was occupied by 100 sheep, hired to eat the grass. Henry Moore, the English sculptor, loved drawing sheep but the large mass of fluffy white things didn’t do it for me. Instead I looked beyond them, attempting to discern an imagined hillside beneath the sea of white in a rapid charcoal sketch. Later that evening, away from the scene, I played over the top with watercolor. I like that it is at once a highly abstract image but at the same time quite clear.

ThV – We share an affinity for Chaïm Soutine, the Russian émigré painter to France, but you have also mentioned Degas and Gauguin. Why are they so important for you?

DI – They are not – no more than many other great artists throughout history I have come to appreciate. Degas was a master in every respect and would be considered great in any era. Soutine was one of those divine, unique oddballs I cannot help but love. Ensor, Arcimboldo and Redon are a few more. Soutine’s work has occasionally been called ugly, but I find them almost heartbreakingly beautiful – and expressive to their core. He was a painter’s painter. Gauguin lived in Denmark once but managed to escape and become what he became. There are many brilliant individuals I respect and find influential: Goya, Klee, Schiele, de Kooning, de Staël… and that doesn’t even begin to scratch the surface.

ThV – Once Europe was the world center for culture, art and artists and there was quite a large market. It does not seem to be the case anymore. In your eyes is this part of the decay of occidental culture?

DI – Now that sounds like a question that artists long ago might have argued over drinks in the cafes of Paris. I can’t say. I tend to blame Hitler, the failed artist. If only he had been better at drawing! Instead we got the Third Reich, war and misery across the continent. For centuries Europe – in particular, Paris – was the seat of all that was great and innovative in western art. The Industrial Revolution transformed Europe and the west. This brave new world acted as a catalyst and gave rise to a tremendous series of changes for decades, reflected in the arts. WWl didn’t stop the juggernaut but WWll did. Afterward, the continent was simply too exhausted… and focused upon rebuilding. NYC became the new Mecca of western art, which it remains to this day.

ThV – One final question: you are quite fond of photography, although you despise the common practice of selfies and everyday snapshots. Do you use it for your paintings and drawings, or do you consider it an “art” in its own right, on the same level? What interests you about it?

DI – At a younger age I employed photography occasionally when I drew. However, I have never used my own photography to work from. That has never once occurred to me to do. It is indeed an art in its own right. Like drawing and painting, it is about vision. It is about seeing and making choices, sometimes in a split second, other times waiting for the ideal moment. Or it could be planning and setting up a long exposure… or double exposure.

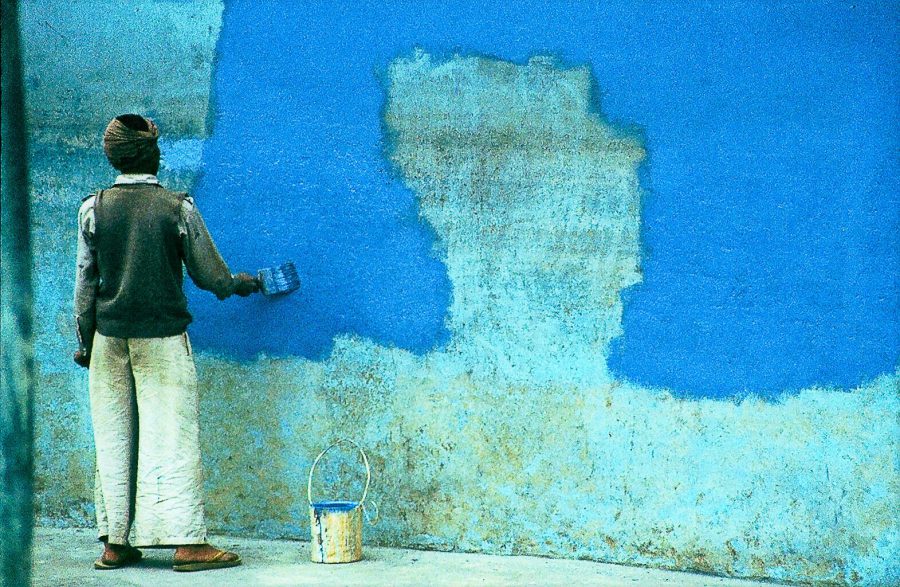

My photography is highly visual, less about telling a story or capturing a memory. More than any single factor, all photos require graphic visual interest, the ability to catch the eye. I particularly enjoy photographing people, usually in some far-flung place – but aside from my taking their picture, we have never met. Patterns and writing on walls, patterns in general, reflections in water – but especially faces – catch my photographic eye. As with anything I do there is a search for beauty at the heart of it… not messages, no politics. Beauty. The world can be a beautiful place.