by Cleto Corposanto & Umberto Pagano

by Cleto Corposanto & Umberto Pagano

In this section all materials and documents useful to submit European projects:

– Documentation for exercises and assignments

– Call for proposals complete documentation

– Public procurement

Formatore e consulente PA nell’ambito delle politiche del lavoro e dell’istruzione e formazione. In particolare, ha sviluppato una lunga carriera nell’ambito di implementazione e gestione dei sistemi regionali di certificazione delle competenze – costruzione di sistemi regionali di standard professionali, formativi e di individuazione, validazione e certificazione delle competenze. Si occupa da oltre vent’anni di progettazione di percorsi di orientamento e formazione per Istituzioni scolastiche, Università e Agenzie formative in ambito nazionale e internazionale.

Professore ordinario presso il dipartimento di sociologia e ricerca sociale dell’Università di Trento, si occupa di organizzazione dei servizi sociali e socio sanitari. Ha studiato sociologia, economia e antropologia in Italia, Germania, Gran Bretagna e Svizzera. Lavora da molti anni sui temi del terzo settore, delle organizzazioni della società civile e della cittadinanza attiva. Ha scritto su questi argomenti molti libri e articoli.

27 maggio ore 10.00

Sociologia UMG Catanzaro

Sources of funding

3 giugno ore 15.00

Piattaforma DiagonalCampus

9 giugno ore 15.00

Incontro meet online

Docenti:

Stefano Morena

Filippo Sestito

10 giugno ore 10.00

Incontro meet online

16 giugno ore 15.00

Piattaforma DiagonalCampus

17 giugno ore 10.00

Incontro meet online

Docenti:

Cleto Corposanto

Luca Fazzi

23giugno ore 15.00

Incontro meet online

Docente:

G. Mirante

24 giugno ore 10.00

Piattaforma DiagonalCampus

30giugno ore 10.00

Sociologia UMG Catanzaro

Docenti e Centro Servizi Volontariato Centro Calabria

Il presente corso è erogato in modalità di auto-formazione. Cos’è? Si tratta di una modalità di apprendimento in cui gli individui assumono la responsabilità principale del proprio processo di acquisizione delle conoscenze. In un contesto di corso online come questo, l’auto-formazione implica che i partecipanti siano i principali protagonisti del loro apprendimento, gestendo autonomamente il proprio percorso formativo.

Nella pratica, l’auto-formazione coinvolge diversi aspetti:

I Vantaggi dell’Apprendimento DiagonalCampus:

Come rendere produttivi i contenuti:

Insegna “Mercato del lavoro e Progettazione sociale” al corso di laurea in Sociologia dell’Università Magna Græcia di Catanzaro.

Sociologo, giornalista professionista dal 1994, è stato Direttore del Cerisdi (Centro di Ricerca e Studi Direzionali) fondato da padre Ennio Pintacuda a Palermo e Direttore Strategico di Crisea (Centro di Ricerca e Servizi Avanzati per l’Innovazione Rurale) in Calabria.

Ha ideato e animato vari Network internazionali, tra cui la rete europea Diagonal.

È il fondatore della piattaforma editoriale web The diagonales (www.diagonales.it) e del Network partecipativo PYou (www.pyou.org).

Il suo ultimo lavoro si intitola “Il progettista sociale. Osservazioni partecipanti” ed è stato pubblicato da Rubbettino Ed.

Project implementation and reporting is an important aspect of project management. In this section we will cover the important administrative, financial and document procedures, the project team and its principles of quality and control.

In this section we will study approaches to project management. In particular we will examine the Logical Framework, management diagrams and aspects related to project evaluation. We will also take care of the budgeting.

Once you have understood the logic of European funds and explored their characteristics, in this section you will explore the main success factors: the project management cycle, the design process phases, stakeholder analysis, tools and methodologies for build a good project.

RIDDLES

Martin Heidegger wrote: “In Angst one has «uncanny» feeling. Here the peculiar indefiniteness of that which Da-sein finds itself involved in with Angst initially finds expression: the nothing and no-where. But uncanniness means in the same time not-being-at-home (…). Everyday familiarity collapses. Da-sein is isolated, but as being-in-the world. Being-in enters the existential «mode» of not-being-at-home. Now, however, what falling prey, as flight, is fleeing from becomes phenomenally visible. It is not a flight from innerworldly beings, but precisely toward them as the beings among which taking care of things. Lost in the they, can linger in tranquillized familiarity. Entangled flight into the being-at-home, that is, from the uncannieness which lies in Da-sein as thrown, as being-in-the-world entrusted to itself in its being. Not-being-at-home (Ex-propriation) must be conceived existentially and ontologically as the more primordial phenomenon (SuZ, §40). Riddles: they either delight or torment. Their delight lies in solutions. Answer provide bright moments of comprehension perfectly suited for children who still inhabit a world where solutions are readily available. Implicit in the riddle’s form is a promise that the rest of the world resolves just as easily. And so riddles comfort the child’s mind which spins wildly before the onslaught of so much information and so many subsequent questions. The adult world, however, produces riddles of a different variety. They do not have answers and are often called enigmas or paradoxes. Still the old hint of the riddle’s form corrupts these questions by re-echoing the most fundamental lesson: there must be an answer. From there comes torment” (Mark Z.Danielewksi).

But, in the specific case, a table, the heat, a cup of coffee, what once was just a phone… may be enough.

And that’s it.

ROMPICAPI

Ha scritto Martin Heidegger: “Nell’angoscia ci si sente «spaesati».

Qui trova espressione innanzitutto la indeterminatezza tipica di ciò dinanzi a cui l’Esserci si sente nell’angoscia: il nulla e l’in-nessun-luogo. Ma sentirsi spaesato significa, nel contempo, non-sentirsi-a-casa-propria. (…). La familiarità quotidiana si dissolve. L’Esserci resta isolato, ma lo è come essere-nel-mondo. L’in-essere assume il «modo» esistenziale del non-sentirsi-a-casa-propria.

Si è così reso visibile fenomenicamente ciò davanti-a-cui la deiezione, in quanto fuga, fugge. Non davanti all’ente intramondano, poiché questo ente è proprio ciò verso cui avviene la fuga, e su cui può soffermarsi il prendersi cura dominato dalla familiarità tranquillizzante e perso nel Si. La fuga deiettiva verso il sentirsi-a-casa propria, cioè davanti a quel sentirsi spaesato che è proprio dell’Esserci in quanto essere-nel-mondo gettato e rimesso a sé stesso nel proprio essere. Dal punto di vista ontologico-esistenziale, il non-sentirsi-a-casa-propria (Es-propriazione) deve essere concepito come il fenomeno più originario” (SuZ, §40).

I rompicapi, croce e delizia. La delizia sta nella soluzione. Le risposte innescano momenti di illuminazione che ben soddisfano i più piccoli, i quali abitano ancora un mondo in cui le soluzioni sono a portata di mano. Implicita nella natura del rompicapo è la promessa che il resto del mondo si possa risolvere altrettanto facilmente.

Così il rompicapo conforta la mente infantile, che vortica dinanzi a tutte quelle informazioni e alle conseguenti domande. Il mondo adulto, tuttavia, produce rompicapi di altro genere, rompicapi privi di risposta che spesso vanno sotto il nome di enigmi o paradossi. D’altro canto la loro tradizionale forma di rompicapo li tradisce riecheggiando la morale fondamentale: una risposta deve esserci. Di qui la croce” (Mark Z.Danielewksi).

Ma, nello specifico, un tavolo, il caldo, una tazzina di caffè, quello che una volta era solo un telefono… possono bastare, forse.

Ecco.

SHARM

There are many borderlands on Earth. Places that act as a watershed between populations, cultures, religions and even very different languages.

I took this photo in one of the most significant border posts. We are in the Sinai peninsula, of a vague triangular shape, approximately 380 km long from North to South and a little more than 200, with a coastal development of about 600. The Sinai, squeezed between the Gulf of Suez and that of Aqaba, it is largely desert territory, except for some seaside resorts including Nuweiba, Dahab and the more famous Sharm el-Sheikh.

The Gulf of Suez acts as a geographical border between Africa and Asia, and this is why the Sinai Peninsula is geographically the first Asian outpost. But administratively it is part of Egypt, representing the last edge of it to the east. In short, it‘s a piece of Africa in Asia. We are talking about a territory that has always been at the center of attention, given that it has long been a contest, for example in the so-called six-day war between Israel and Egypt, in fact. Conquered by the government of Jerusalem in 1967, it was returned to Egypt thanks to the Camp David agreements, 11 years later.

In short, a real border post.

A place where, thanks also to an important tourist development for many years, exogenous and endogenous cultures and customs are intertwined, where apparently irreconcilable lifestyles coexist. I took this photo in Sharm el-Sheikh, along a road that leads to the sea from one of the many tourist villages frequented by tourists who love the climate and the richness of the fauna of the marine waters. Those villages where, almost thanks to a tacit agreement, during the day the pools are reserved for foreign tourists – and the Russians, as well as the Italians, abound there – while at night the Arab women make use of them, dressed in their jilbabs.

A photo that exactly testifies to the proximity of the many cultures that, in Sinai, coexist with mutual respect: four women, each with different clothing, are going to the beach. Let’s imagine that everyone is at ease in their culture, respecting some principles, in the choice of clothing. Such a large assortment is rare at the same time. It only happens in border posts, where everything mixes.

SHARM

Ci sono molti territori di confine sulla Terra. Posti che fanno da spartiacque fra popolazioni, culture, religioni e lingue anche molto diverse fra loro.

Ho scattato questa foto in uno dei posti di confine più significativi. Siamo nella penisola del Sinai, di vaga forma triangolare, lunga all’incirca 380 km da Nord a Sud e larga poco più di 200, con uno sviluppo costiero di circa 600. Il Sinai, stretto fra il golfo di Suez e quello di Aqaba, è in gran parte territorio desertico, se si eccettuano alcune località marittime tra le quali Nuweiba, Dahab e la più famosa Sharm el-Sheikh. Il golfo di Suez fa da confine geografico fra Africa e Asia, ed è per questo quindi che la penisola del Sinai, geograficamente è il primo avamposto asiatico. Ma amministrativamente fa invece parte dell’Egitto, rappresentandone l’ultimo lembo a est. E’, insomma, un pezzo di Africa in Asia. Parliamo di un territorio da sempre al centro dell’attenzione, visto che è stato al lungo conteso, per esempio nella cosiddetta Guerra dei sei giorni tra Israele ed Egitto, appunto. Conquistata dal governo di Gerusalemme nel 1967, fu restituita all’Egitto grazie agli accordi di Camp David, 11 anni dopo.

Un vero posto di confine, insomma. Un luogo dove, complice anche uno sviluppo turistico importante già da moltissimi anni, si intrecciano culture ed usanze esogene ed endogene, dove convivono stili di vita apparentemente inconciliabili. Ho scattato questa foto a Sharm el-Sheikh, lungo una stradina che porta al mare da uno dei tanti villaggi turistici frequentatissimi dai turisti che amano clima e ricchezza della fauna delle acque marine. Quei villaggi dove, quasi grazie ad un tacito accordo, durante il giorno le piscine sono riservate ai turisti stranieri – e abbondano i russi, oltre che gli italiani, da quelle parti – mentre nelle ore notturne sono le donne arabe a fare uso delle stesse, vestite con i loro jilbab.

Una foto che testimonia esattamente la prossimità delle tante culture che, nel Sinai, convivono con reciproco rispetto: quattro donne, ciascuna con un abbigliamento differente, stanno andando al mare. Immaginiamo che ciascuna si trovi a proprio agio nella sua cultura, nel rispetto di alcuni principi, nella scelta dell’abbigliamento. Un così vasto assortimento è raro nello stesso momento. Accade solo nei posti di confine, dove tutto si mescola.

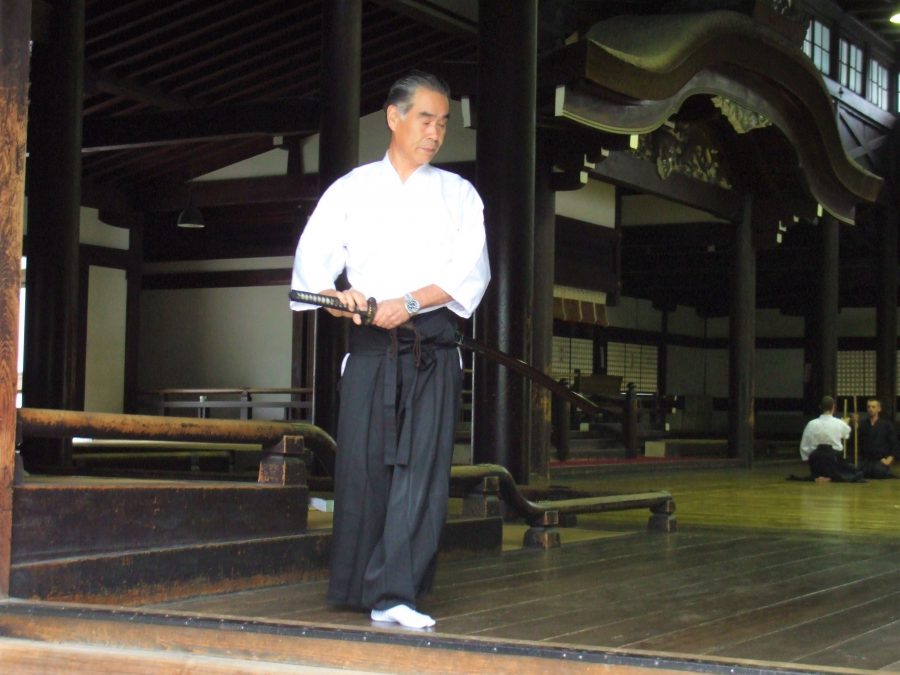

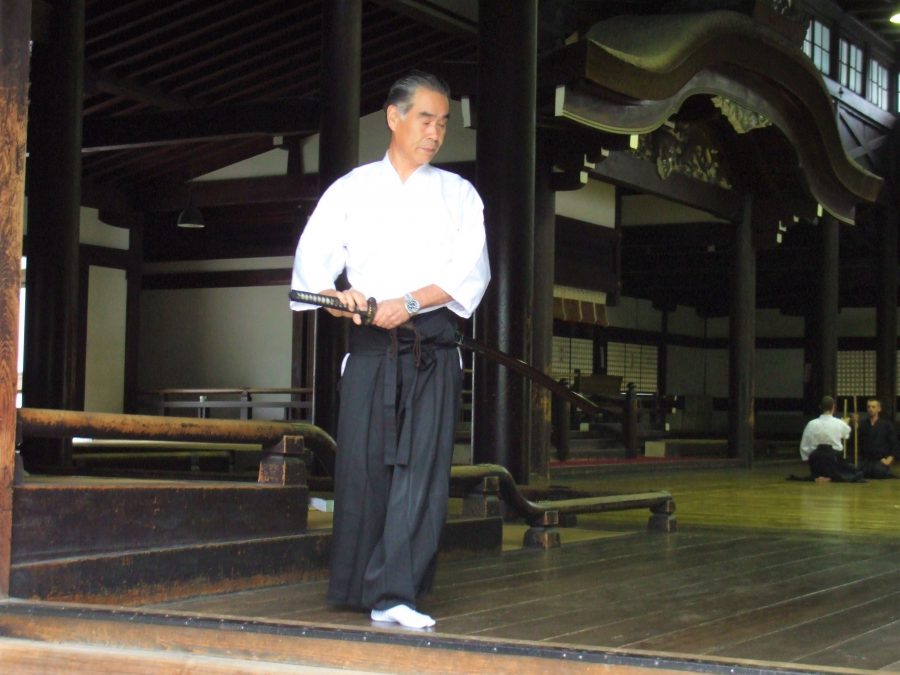

THE WAY OF THE SWORD

I took this photo in dōjō [note 1] in Kyoto, intended for the practice of Kendō.

The «Kendō» is «the way of the sword», the ancient Japanese autochthonous martial art (the only one together with Sumo) derived from the evolution of the techniques of use of katana, the Samurai sword. But for long time now the katana has been replaced by the shinai, a sort of bamboo sword.

Tinking of Kendō in western terms, as a combat practice, would mean being very far from the real meaning it has in Japanese life, in which it represents one of the greatest expressions of Zen.

It is inspired by principles of loyalty, discipline, overcoming fear, enduring suffering, modesty. But above all Kendō tends to “emptiness”, that is, it aspires to create the mental void (mushin), which is the presupposition of enlightenment (Satori).

Western thought tends to be dualistic, proceeds in pairs of opposites, while for Zen understanding is non-absolute, non-conceptual, inexpressible through words, and arises in the void, above being and non-being, in a higher dimension of “no-mind”.

To totally master the sword, the technique is not enough at all, you have to get to its spirit, and this is possible only by reaching the no-mind, the (in)consciousness beyond good and evil, true and false, in short, beyond of the trap of opposites. It is a condition unachievable and incomprehensible through rational logic. In fact, Zen is not taught, it is lived; it is not theory, it is only – and totally – a practice.

From outside of the Japanese culture, the “way of the sword” may seem absurd, paradoxical: the practitioner aspires to reach a state of mental detachment but at the same time a dynamic and harmonious tension of every muscle in the body, as long as all its movements will no longer be governed by logical-rational thinking.

No matter how hard he tries, a westerner will never really understand Kendō. But it is impossible not to be fascinated and overwhelmed by the rituality with which it is deeply imbued.

Just think of the system of “degrees” that express the level of skill reached by the practitioner[note 2]. There are seven initial degrees (Kyū) and eight higher degrees (Dan). To reach the 8th dan it is necessary to be at least 46 years old and have 31 years and 3 months of practice of the discipline, as well as having achieved the 7th dan for at least 10 years. The exam to reach the last dan is considered one of the hardest tests in the world, with a passing rate of around 0.5%. About 1,500 practitioners try it every year, but only 6 or 7 succeed. Every dan has its name. The eighth and final dan is called «Hachi». A rather indicative term: it means «God of Kendō».

[1] In Japanese language «dōjō» indicates the «place where the Way is taught», that is, the way to get to the open-minded condition to which Zen tends. Both rooms dedicated to meditation and those in which martial arts are practiced take this name.

[2] Contrary to other martial arts, the “degree” is not expressed through the “color” of a belt, nor through any other sign. It has no external manifestation at all.

LA VIA DELLA SPADA

Ho scattato questa foto in un dōj [nota 1] di Kyoto, destinato alla pratica del Kendō.

Il «Kendō» è «la via della spada», l’antichissima arte marziale autoctona giapponese (l’unica insieme al Sumo) derivata dalla evoluzione delle tecniche di uso della katana, la spada dei Samurai. Ma ormai da tempo la katana è stata sostituita dallo shinai, una sorta di spada di bambù.

Pensare al Kendō in termini occidentali, come pratica di combattimento, significherebbe essere molto lontani dal significato reale che esso assume nella vita giapponese, in cui rappresenta una delle massime espressioni dello Zen.

È ispirato a principi di lealtà, disciplina, superamento della paura, sopportazione della sofferenza, modestia. Ma soprattutto il Kendō tende alla “vacuità”, aspira cioè a creare il vuoto mentale (mushin), il presupposto dell’illuminazione (Satori).

Il pensiero occidentale è tendenzialmente dualistico, procede per coppie di opposti, mentre per lo Zen la comprensione è non-assoluta, non-concettuale, inesprimibile con parole, e si pone nel vuoto, al di sopra dell’essere e del non essere, in una superiore dimensione di “non-mente”.

Per padroneggiare totalmente la spada non basta affatto la tecnica, bisogna arrivare al suo spirito, e ciò è possibile solo raggiungendo la non-mente, l’(in)coscienza che pone al di là del bene e del male, del vero e del falso, al di là della trappola degli opposti insomma. È uno stato che non può realizzarsi né comprendersi attraverso al logica razionale. Infatti, lo Zen non si insegna, si vive; non è teoria, è solamente – e totalmente – pratica.

Dall’esterno della cultura giapponese, la “via della spada” può sembrare assurda, paradossale: il praticante aspira a giungere ad uno stato di distacco mentale ma nel contempo di tensione dinamica e armonica di ogni muscolo del corpo, fin quando tutti i suoi movimenti saranno governati non più dal pensiero logico-razionale.

Per quanto ci possa provare, un occidentale non riuscirà mai a comprendere il Kendō. Ma non si può che rimanere affascinati e sopraffatti dalla ritualità di cui è profondamente intriso.

Basti pensare al sistema dei “gradi” che esprimono il livello di abilità raggiunto dal praticante [nota 2]. Esistono sette gradi inziali (Kyū) e otto gradi superiori (Dan). Per raggiungere l’8o dan è necessario avere almeno 46 anni di età e 31 anni e 3 mesi di pratica della disciplina, nonché aver conseguito il 7° dan da almeno 10 anni. L’esame per raggiungere l’ultimo dan è considerato una delle prove più difficili al mondo, con una tasso di superamento intorno allo 0,5%. Ogni anno ci provano circa 1500 praticanti, ma solo in 6 o 7 lo superano. Ogni dan ha un nome. L’ottavo e ultimo dan si chiama «Hachi». Un termine piuttosto indicativo: significa «Dio del Kendō».

[1] In Giapponese «dōjō» sta ad indicare il “luogo dove si insegna la Via”, cioè il modo di arrivare alla condizione apertura mentale cui tende lo Zen. Prendono questo nome sia le sale dedicate alla meditazione sia quelle in cui si praticano le arti marziali.

[2] Contrariamente alle altre arti marziali il “grado” non si esprime attraverso il “colore” di una cintura, né attraverso alcun altro segno. Esso non ha alcuna manifestazione esterna.

DOCTOR LIVINGSTONE, I PRESUME

“Doctor Livingston, I presume” is a phrase that has somehow remained in history. Lovers of great travel and travelers know it very well, but it has become part of the lexicon of many others, even those who consider travel from home to sea as the maximum possible travel.

The sentence was pronounced on November 10, 1871, by the well-known journalist and explorer Henry Morton Stanley – Welshman by birth and American by adoption – in Ujiji, an ancient city in Tanzania located on the shores of Lake Tanganyika. In front of him was David Livingstone, physician, missionary and explorer of Scottish origins. Two intricate stories, one in front of the other.

Henry Morton Stanley was born as John Rowlands, in Denbigh in Northeastern Wales, in 1841. An illegitimate son, he never knew from his mother – who entrusted him to an orphanage – who his father was. When he was 17 years old, he embarked for New Orleans to begin his second life as an American citizen, at first becoming an archivist and freelance journalist later.

It was only in 1869 that it was decided to send someone in search of him, and the choice fell precisely on Henry Morton Stanley, who in turn faced the journey in the black continent on the trail of Livingstone, managing to track him down after two years. It was, precisely, November 10, 1871; and as if they were two friends they did not see each other, they greeted each other as if they had met by chance at a dinner. In fact, they were probably the only two non-African men within hundreds of kilometers. Livingston died two years later, in 1873, from malaria.

This photo was taken in Livingstone, a city that took its name from the great European explorer, in present-day Zambia (formerly northern Rhodesia).

The city, just beyond the border with Zimbabwe, is about ten kilometers from Victoria Falls and between 1911 and 1935 it was also the capital of the then English colony, before the headquarters were moved to Lusaka.

In Livingstone, today, it is possible to visit a small museum linked to the adventurous life of this great traveler, who in Africa chose to live and die. An interesting place for a great traveler, an obligatory stop after admiring, entranced, the splendor of nature represented by the Victoria Falls.

DOCTOR LIVINGSTONE, I PRESUME

“Dottor Livingston, I presume” è una frase in qualche modo rimasta nella storia. La conoscono molto bene gli appassionati di grandi viaggi e viaggiatori, ma è entrata a far parte del lessico di molti altri, anche di quelli che considerano il viaggio da casa a mare come il massimo degli spostamenti possibili.

La frase la pronunciò, il 10 novembre 1871, il noto giornalista ed esploratore Henry Morton Stanley – gallese di nascita e americano di adozione – a Ujiji, antica città della Tanzania posta sulle rive del lago Tanganica. Difronte a lui c’era, appunto, David Livingstone, medico, missionario ed esploratore di origini scozzesi. Due storie intricate, una difronte all’altra.

Henry Morton Stanley nacque come John Rowlands, a Denbigh nel Galles nord-orientale, nel 1841. Figlio illegittimo, non seppe mai da sua madre – che lo affidò ad un orfanotrofio – chi fosse suo padre. A 17 anni si imbarcò con destinazione New Orleans, per cominciare la sua seconda vita come cittadino americano, fino a diventare archivista prima e giornalista freelance poi.

Fu solo nel 1869 che si decise di inviare qualcuno alla sua ricerca, e la scelta cadde proprio su Henry Morton Stanley, che affrontò a sua volta il viaggio nel continente nero sulle tracce di Livingstone, riuscendo dopo due anni a rintracciarlo. Era, appunto, il 10 Novembre 1871; e come se fossero due amici non si vedevano da poco, si salutarono come se si fossero incontrati per caso ad una cena. In realtà, erano probabilmente gli unici due uomini non africani nel raggio di centinaia di chilometri. Livingston morirà due anni dopo, nel 1873, di malaria.

Questa foto è stata scattata a Livingstone, città che ha preso il nome proprio dal grande esploratore europeo, nell’attuale Zambia (ex Rhodesia settentrionale). La città, poco al di là del confine con lo Zimbabwe, dista una decina di chilometri dalle cascate Victoria e tra il 1911 e il 1935 fu anche capitale dell’allora colonia inglese, prima che la sede fosse spostata a Lusaka.

A Livingstone, oggi, è possibile visitare un piccolo museo legato alla vita avventurosa di questo grande viaggiatore, che in Africa scelse di vivere e di morire. Un posto interessante per un grande viaggiatore, una tappa obbligata dopo aver ammirato, estasiato, quello splendore della natura rappresentato dalle cascate Victoria.

[contact-form-7 id=”1831″ title=”Modulo di contatto diameter”]

If I had to express Myanmar with one word, I would say dazzling. In this way this country of Southeast Asia appeared to me, the same one I learned about school books as Burma, with the capital of Rangoon. Since 2010, on the other hand, it is called Myanmar – to be exact, the full name is ပြည်ထောင်စု သမ္မတ မြန်မာနိုင်ငံတော်, Pyidaunzu Thanmăda Myăma Nainngandaw – and the capital has become Naypyidaw, a city of just over a million inhabitants north of Yangon (the “old” Rangoon), which still remains the most densely populated and most fascinating urban agglomeration in the whole country. For some time, referring to this nation with the name Burma (which recalls the past from a former British colony, albeit not part of the Commonwealth, until the proclamation of independence in 1948) or with that of Myanmar meant to marry, in some way, a precise political ideology; this even if Burma or Myanmar may appear very different as names if we use our Latin characters, while they have the same root – and also a similar sound – if you use the Abugida writing system, which is precisely the one in use in the country.

The history of this wonderful country is, as often happens, full of problems and even violent political battles to make one’s opinion prevail. There are numerous episodes concerning Myanmar from this point of view, most of which are related to Aung San Suu Kyi, Nobel Peace Prize winner in 1991, after the military junta, the year before, had canceled the elections who had seen her triumph with her “National League for Democracy” list. Aung San Suu Kyi used the prize money to establish a health and education system for the Burmese people. Forced for many years to house arrest, it has become a symbol of the fight against oppression, which over the years has also developed through the so-called “saffron revolution” (from the color of the robes of the Buddhist monks who numerous took part in the non-violent protests attributable to the galaxy of “colored revolutions” that characterized many post-communist regimes).

One of the most majestic and mystical places of Burma / Myanmar at the same time is located in Yangon / Rangoon. I’m talking about the Shwedangon Pagoda (ရွှေတိဂုံစေတီတော် in Burmese) a complex that characterizes the city skyline, visible even at long distance. It is a golden Stupa almost 100 meters high and represents the main Buddhist temple for Burmese, as there are the relics of 4 Buddhas of the past, including Gautama, the historical Buddha.

The Stupa is plated with over twenty thousand solid gold plates and the tip is encrusted with jewels: 5,448 diamonds, plus 2,317 rubies, sapphires and other precious stones and 1,065 gold bells. At the top there is a 76 carat diamond. The pagoda is surrounded by 64 “small” pagodas and 4 other pagodas that indicate the cardinal points.

Inside there is a huge statue of Buddha, made in 1999 with 324 kg of massive jade from the Kachin, an area located in northern Myanmar. This immense Buddha is inlaid with 91 rubies, 9 diamonds and 2.5 kg of gold.

Clear now why the term I associate with Burma is dazzling?

I took this photo in one of the thousand places inside the Shwedangon Pagoda. I really liked the light that emanated and the color – gold – everywhere, even in the clothes of this young Burmese woman. It is a photo of the end of 2019, when the climate – non-meteorological – in the country was good and favored the influx of people from all over the world. A beautiful place. Of a dazzling beauty.

Se dovessi esprimere il Myanmar con una sola parola, direi accecante. Così mi è apparso questo paese del sud-est asiatico, lo stesso che sui libri di scuola avevo imparato a conoscere come Birmania, con capitale Rangoon. Dal 2010 invece, appunto, si chiama Myanmar – per esattezza il nome completo è ပြည်ထောင်စု သမ္မတ မြန်မာနိုင်ငံတော်, Pyidaunzu Thanmăda Myăma Nainngandaw – e la capitale è diventata Naypyidaw, città di poco più di un milione di abitanti a nord di Yangon ( la “vecchia” Rangoon), che resta comunque l’agglomerato urbano di gran lunga più popolato e con maggior fascino di tutto il paese. Per diverso tempo, riferirsi a questa nazione con il nome Burma (che rievoca il passato da ex colonia britannica, seppur non parte del Commonwealth, fino alla proclamazione di indipendenza del 1948) oppure con quello di Myanmar ha significato sposare, in qualche modo, un’ideologia politica precisa; questo anche se Burma o Myanmar possono apparire molto differenti come nomi se utilizziamo i nostri caratteri latini, mentre hanno la stessa radice – e anche un suono simile – se si utilizza il sistema di scrittura abugida, che è appunto quello in uso localmente.

La storia di questo meraviglioso paese è, come spesso accade, ricca di problemi e battaglie politiche anche violente per far prevalere la propria opinione. Sono numerosi gli episodi che riguardano da questo punto di vista il Myanmar, la maggior parte dei quali sono legati ad Aung San Suu Kyi, premio Nobel per la pace nel 1991, dopo che la giunta militare, l’anno prima, aveva annullato le elezioni che l’avevano vista trionfare con la sua lista “Lega nazionale per la democrazia”. Aung San Suu Kyi usò i soldi del premio per costituire un sistema sanitario e di istruzione a favore del popolo birmano. Costretta per lunghi anni agli arresti domiciliari, è diventata un simbolo della lotta all’oppressione, che negli anni si è sviluppata anche per mezzo della cosiddetta “rivoluzione zafferano” (dal colore delle tonache dei monaci buddisti che numerosi hanno preso parte alle proteste non violente riconducibili alla galassia delle “Rivoluzioni colorate” che hanno caratterizzato molti regimi post-comunisti).

Uno dei luoghi più maestosi e mistici, allo stesso tempo, di tutta la Birmania/Myanmar, si trova proprio a Yangon/Rangoon. Sto parlando della Pagoda Shwedangon ( ရွှေတိဂုံစေတီတော် in birmano), un complesso che caratterizza lo skyline della città, visibile anche a lunga distanza. Si tratta di uno Stupa dorato alto quasi 100 metri e rappresenta il tempio buddista principale per i birmani, in quanto lì sono custodite le reliquie di ben 4 Buddha del passato incluso Gautama, il Buddha storico.

Lo stupa è placcato con oltre ventimila lastre d’oro massiccio e la punta è incrostata di gioielli: 5.448 diamanti, più 2.317 rubini, zaffiri e altre pietre preziose e 1.065 campane d’oro. Al vertice c’è un diamante di 76 carati. La pagoda è circondata da 64 “piccole” pagode e da altre 4 pagode che indicano i punti cardinali.

All’interno si trova una statua enorme di Buddha, realizzata nel 1999 con 324 kg di giada massiccia proveniente dal kachin, una zona che si trova nel nord del Myanmar. Questo immenso Buddha è intarsiato con 91 rubini, 9 diamanti e con 2,5 kg di oro.

Chiaro ora perché il termine che associo alla Birmania è accecante?

Ho scattato questa foto proprio in uno dei mille posti all’interno della Pagoda Shwedangon. Mi piaceva molto la luce che emanava e il colore – oro – dappertutto, anche nei vestiti di questa giovane birmana. E’ una foto della fine del 2019, quando il clima – non meteorologico – nel Paese era buono e favoriva l’afflusso di gente da tutto il mondo. Un posto bellissimo. Di una bellezza accecante.

DUPLICATIONS, INTERSECTIONS

A photo of a photo exhibited in the palace of the popes in Avignon.

The picture photographed shows the poster of a Pietà representing a “double” Pasolini, who personifies both the dead Christ and the one who holds it in his arms. French street-artist Ernest Pignon Ernest made this poster and went around pasting it in many places of many Italian cities, places for themselves, for one reason or another, densely symbolic, taking a photo of each poster glued and of scenario around it, and eventually exhibited those photos around the world.

In Pier Paolo Pasolini’s work, an intimate, close, recursive comparison with the figure of Christ is evident. His “Il Vangelo secondo Matteo” (The Gospel According to St. Matthew) represents the attempt of an atheist who is confronting with the mystery aspects of existence but also with the more human and anarchist sides of the social “construction” of Christ, in which the “true” story matters very little and the theological-dogmatic apparatus matters nothing. Instead, all is about the specularity between the experience of Pasolini and the one of Christ in bringing a “revolutionary” word to the derelicts and oucasts. Pasolini himself in a famous interview with the “Nouvel Observateur”, in March 1965, said: “Some laymen told me that my Christ is Stalinist. In fact, I was thinking of Lenin! The fact is that they do not take into account that Christ proposes himself as the son of God, and the cult of personality is a bit like this: to deify a man”.

There is a measure of magnetic and magmatic power in this unsettling tragic hyperrealism of a secular Piety in which PPP carries his own corpse in his arms, in a deafening doubling of pain. And the poster, a technical reproduction, duplicates, triples, multiplies and spreads in a thousand places. And photography, double par excellence, which im-mortalise (takes away from mortality, from the fleeting moment) the death of the Christ-Pasolini and his dead body carried by his own double. And a Neapolitan who, in his turn, in Avignon, photographs, doubles, the photo that portrays the poster of Piety of Pasolini affixed on a wall of a devastated and devastatingly poetic Scampia (Naples).

And how can we forget that PPP himself had duplicated, replicated, for lighting and image composition, the Mantegna’s dead Christ, in the penultimate, astonishing sequence of his Mamma Roma?

So many duplications. And intersections.

DUPLICAZIONI, INTERSEZIONI

Una foto di una foto esposta nel palazzo dei papi di Avignone.

La foto fotografata ritrae il poster di una Pietà che rappresenta un Pasolini “doppio”, che impersona sia il Cristo morto che chi lo tiene in braccio. Lo street-artist francese Ernest Pignon Ernest ha realizzato questo poster ed è andato in giro ad incollarlo in molti luoghi di tante città italiane, luoghi per sé, per un motivo o per un altro, densamente simbolici, avendo cura di scattare una foto a ogni poster incollato e a ciò che lo circonda, per poi esporle in giro per il mondo.

Nell’opera di Pier Paolo Pasolini è evidente un confronto intimo, serrato, ricorsivo con la figura di Cristo. Il suo Vangelo secondo Matteo rappresenta il tentativo di un ateo che si confronta con gli aspetti misterici dell’esistenza ma anche con i lati più umani e anarchici della “costruzione” sociale del Cristo, in cui la storia “vera” c’entra poco e l’apparato teologico-dogmatico nulla. C’entra invece la specularità tra l’esperienza pasoliniana e quella cristica nel portare una parola “rivoluzionaria” ai derelitti, agli emarginati, agli ultimi. Lo stesso Pasolini in una famosa intervista al «Nouvel Observateur», nel marzo del ’65, disse: “Certi laici mi hanno detto che il mio Cristo è stalinista. In effetti io pensavo a Lenin! Il fatto è che i laici non tengono conto che Cristo si propone come figlio di Dio, e il culto della personalità è un po’ questo: divinizzare un uomo”.

C’è una misura di potenza magnetica e magmatica in questo spiazzante iperrealismo tragico di una Pietà laica in cui PPP porta in braccio il sul stesso cadavere, in un assordante raddoppiamento del dolore. E il poster, riproduzione tecnica, che si duplica, si triplica, si moltiplica e si diffonde in mille luoghi. E la fotografia, doppio per eccellenza, che im-mortala, (che sottrae alla mortalità, alla fugacità dell’attimo) la morte del Cristo-Pasolini, portato dal suo doppio.

E un napoletano che ad Avignone, fotografa a sua volta – raddoppia – la foto che ritrae il poster della Pietà di Pasolini affisso ad un muro di una Scampia (Napoli) devastata e devastatamente poetica.

E come non ricordare che lo stesso PPP aveva duplicato, replicato, per illuminazione e composizione d’immagine, il Cristo morto del Mantegna, nella penultima sbalorditiva sequenza del suo Mamma Roma?

Quante duplicazioni. E intersezioni.

QUELLE NUBI SU HONG KONG

Hong Kong è uno degli spartiacque del mondo.

E’ uno di quei posti che fanno venire in mente snodi cruciali nella storia dell’uomo. O che rievocano immagini di mondi tangenti, come il Capo di Buona Speranza dei tanti racconti sui grandi viaggi in mare. Inizialmente riferito ad una piccola insenatura sull’isola, il nome Hong Kong rappresenta – come la maggior parte dei nomi di origine cinese – un’approssimativa rappresentazione fonetica di “香港”, Hakka, che significa Porto Profumato.

E’ possibile che il nome derivi dalle fabbriche di incenso presenti nella zona. Col tempo, a partire dal 1842, il nome Hong Kong è diventato prima quello dell’intera isola; e poi pian piano – in un arco temporale che va dal 1860 al 1898 – ha inglobato prima la penisola di Kowloon e poi quello dei territori prospicienti sulla terraferma.

Hong Kong divenne una colonia britannica subito dopo la cosiddetta prima guerra dell’Oppio (1839-1842); un periodo di lunga indipendenza dalla Cina concluso a Luglio del 1997, quando dopo 156 anni di colonialismo britannico la sovranità di Hong Kong venne trasferita dal Regno Unito alla Repubblica Popolare Cinese, diventando di fatto la prima regione amministrativa speciale della Cina.

Da allora, Hong Kong ha dovuto fare i conti con molti problemi: immediatamente dopo il passaggio alla Cina, ha prima subito la grave crisi dei mercati finanziari asiatici e poi la gravissima epidemia di influenza aviaria H5N1. Qualche anno dopo, nel 2003, è stata la famigerata SARS (la sindrome acuta respiratoria severa) a colpire la popolazione di Hong Kong. E’ anche per questo che mi è tornata in mente in questi giorni di pandemia.

Ho scattato questa foto dall’alto del Peak, uno dei punti di osservazione più belli di Hong Kong, verso la fine del 2018. La città appare in tutta la sua straordinaria bellezza, lasciando intuire il primato mondiale della presenza di grattacieli, che sono oltre 1300.

La particolare orografia e la mancanza di spazio hanno reso Hong Kong la città più verticale del mondo. Non sono stato fortunatissimo: quel giorno, come si può vedere, il cielo era coperto ma non al punto da privarmi di una delle viste più belle al mondo. Ecco, queste fosche nubi su Hong Kong per me oggi rappresentano simbolicamente la situazione difficile e non chiara che l’ex colonia britannica sta vivendo.

Dallo scorso anno è iniziato un nuovo ciclo di proteste per “mantenere le distanze” da un Paese che sta diventando sempre più presente nei delicati equilibri di Hong Kong. Una serie di proteste molto veementi, che hanno visto scendere in piazza un numero impressionante di persone.

Val la pena di ricordare che il 95% della popolazione di Hong Kong è di origine cinese. Eppure, quegli oltre 150 anni di cultura europea, hanno forse segnato in maniera definitiva il loro senso di appartenenza.

QUELLE NUBI SU HONG KONG

Hong Kong è uno degli spartiacque del mondo.

E’ uno di quei posti che fanno venire in mente snodi cruciali nella storia dell’uomo. O che rievocano immagini di mondi tangenti, come il Capo di Buona Speranza dei tanti racconti sui grandi viaggi in mare. Inizialmente riferito ad una piccola insenatura sull’isola, il nome Hong Kong rappresenta – come la maggior parte dei nomi di origine cinese – un’approssimativa rappresentazione fonetica di “香港”, Hakka, che significa Porto Profumato.

E’ possibile che il nome derivi dalle fabbriche di incenso presenti nella zona. Col tempo, a partire dal 1842, il nome Hong Kong è diventato prima quello dell’intera isola; e poi pian piano – in un arco temporale che va dal 1860 al 1898 – ha inglobato prima la penisola di Kowloon e poi quello dei territori prospicienti sulla terraferma.

Hong Kong divenne una colonia britannica subito dopo la cosiddetta prima guerra dell’Oppio (1839-1842); un periodo di lunga indipendenza dalla Cina concluso a Luglio del 1997, quando dopo 156 anni di colonialismo britannico la sovranità di Hong Kong venne trasferita dal Regno Unito alla Repubblica Popolare Cinese, diventando di fatto la prima regione amministrativa speciale della Cina.

Da allora, Hong Kong ha dovuto fare i conti con molti problemi: immediatamente dopo il passaggio alla Cina, ha prima subito la grave crisi dei mercati finanziari asiatici e poi la gravissima epidemia di influenza aviaria H5N1. Qualche anno dopo, nel 2003, è stata la famigerata SARS (la sindrome acuta respiratoria severa) a colpire la popolazione di Hong Kong. E’ anche per questo che mi è tornata in mente in questi giorni di pandemia.

Ho scattato questa foto dall’alto del Peak, uno dei punti di osservazione più belli di Hong Kong, verso la fine del 2018. La città appare in tutta la sua straordinaria bellezza, lasciando intuire il primato mondiale della presenza di grattacieli, che sono oltre 1300.

La particolare orografia e la mancanza di spazio hanno reso Hong Kong la città più verticale del mondo. Non sono stato fortunatissimo: quel giorno, come si può vedere, il cielo era coperto ma non al punto da privarmi di una delle viste più belle al mondo. Ecco, queste fosche nubi su Hong Kong per me oggi rappresentano simbolicamente la situazione difficile e non chiara che l’ex colonia britannica sta vivendo.

Dallo scorso anno è iniziato un nuovo ciclo di proteste per “mantenere le distanze” da un Paese che sta diventando sempre più presente nei delicati equilibri di Hong Kong. Una serie di proteste molto veementi, che hanno visto scendere in piazza un numero impressionante di persone.

Val la pena di ricordare che il 95% della popolazione di Hong Kong è di origine cinese. Eppure, quegli oltre 150 anni di cultura europea, hanno forse segnato in maniera definitiva il loro senso di appartenenza.

BUT HOW DOES JORDAN DO IT?

Jordan is a strange country. If you think about it, you end up being surprised that it still exists. In some ways it is almost a geopolitical paradox that the small Ashemite kingdom manages not only to survive but also to maintain a troubled balance and a certain stability, uncomfortably embedded as it is between Israel, the West Bank, Syria, Iraq and the ‘Saudi Arabia.

It is a land that drips history from each and every stone. Here, on the eastern bank of the Jordan, many biblicists locate the Garden of Eden, and the events of Abraham, Job, Moses. Here, in Bethany, John the baptizer bathed the head of his disciples and of a certain Jesus Christ.

Anyone in Europe who complains about the excessive flow of migrants should take a look at Jordan’s numbers. About 10 million people live here, of whom 3 million are refugees: many Palestinians but also Iraqis and, in recent years, obviously, a huge amount of Syrians, piled up in dusty and desperate camps. It is the country in the world with the highest percentage of refugees over population. And again, you wonder how Jordan keeps going.

Here life, for many, is really hard.

Around here, in many areas, an entire age of life, adolescence, is skipped. Boys seem not to exist: you are child or you are adult. And you often become adult tremendously early.

In Jordan child labour is widespread. It is difficult to have certain numbers. The most accredited estimates report of about 70,000 children exploited in 2016 (they were around 44,000 in 2010, when I visited the country). Jordan formally adheres to international conventions and the law punishes the exploitation of minors with severe penalties. But in reality, the few inspectors often close one eye and the other in front of irregularities. “What a barbarity!”, therefore thinks the wise western man, “What an absurdity!”. What the western wise man does not imagine is that inspectors tolerate violations because not doing so would not mean protecting children, but condemning them to hunger and often to death. They have to work to survive.

I took this photo ten years ago, in March 2010, in Jaresh, a place so full of Roman ruins, about an hour from Amman, on the road to Damascus. I only stayed a few minutes with this shepherd boy and his goats, but I often think of him. Now, ten years after that, he should have just come of age to work. And I think to myself … but how does Jordan do it?

MA LA GIORDANIA COME FA?

La Giordania è uno strano Paese. Se ci si riflette, si finisce per sorprendersi che ancora esista. Per certi versi è quasi un paradosso geopolitico che il piccolo regno ashemita riesca non sono a sopravvivere ma anche a mantenere un pur travagliato equilibrio e una certa stabilità, scomodamente incastonato com’è tra Israele, la Cisgiordania, la Siria, l’Iraq e l’Arabia Saudita.

È una terra che gronda storia da ogni pietra. Qui, sulla sponda orientale del Giordano molti biblisti localizzano il Giardino dell’Eden, e le vicende di Abramo, di Giobbe, di Mosè. Qui, a Betania, Giovanni il battezzatore bagnava il capo ai suoi discepoli e ad un certo Gesù Cristo.

Chi in Europa si lamenta dell’eccessivo flusso di migranti, dovrebbe buttare un occhio ai numeri della Giordania. Qui vivono circa 10 milioni di persone, di cui 3milioni sono profughi e rifugiati: tantissimi palestinesi ma anche iracheni e, negli ultimi anni, ovviamente, un mare di siriani, ammassati in campi polverosi e disperati. È il Paese con la più alta percentuale al mondo di rifugiati in relazione alla popolazione. E di nuovo ti chiedi come faccia la Giordania ad andare avanti.

Qui la vita, per tanti, è veramente dura.

Da queste parti, in molte aree, una intera età della vita, l’adolescenza, si salta. I ragazzi sembrano non esistere: o si è bambini o si è adulti. E spesso si diventa adulti tremendamente presto.

Il lavoro minorile in Giordania è diffusissimo. Difficile disporre di numeri certi. Le stime più accreditate parlano di circa 70.000 bambini sfruttati nel 2016 (erano circa 44.000 nel 2010, quando ho visitato il Paese). Formalmente la Giordania aderisce alle convenzioni internazionali in materia e la legge punisce lo sfruttamento dei minori con pene severe. Ma in realtà, i pochi ispettori spesso chiudono un occhi e l’altro pure di fronte alle irregolarità. “Cha barbarie!”, pensa dunque il giudicante occidentale, “che assurdità!”. Quello che il giudicante occidentale non sa è che gli ispettori tollerano le violazioni perché non farlo non significherebbe proteggere i bambini, ma condannarli alla fame e spesso alla morte. Devono lavorare per sopravvivere.

Questa foto l’ho scattata dieci anni fa, nel marzo del 2010, a Jaresh, un posto pieno zeppo di rovine romane, ad un’oretta da Amman, sulla via per Damasco. Sono rimasto solo pochi minuti con questo bambino pastore e le sue capre, ma spesso ci ripenso. Ora, dopo dieci anni da allora, dovrebbe appena aver compiuto l’età per lavorare. E tra me e me, penso… ma la Giordania come fa?

Cities are full-colour or black and white. It is a condition that has little to do with real colours of things but rather with their “soul”.

By my nature and aesthetic orientation, with some exceptions, I am more attracted to black and white cities. And not surprisingly, the clearest pictures in my mind are black and white.

Bangkok is a colour city. San Francisco, Rangoon, Mexico City are colour. Instead, Berlin, Paris, Prague (at least the one before the devastating disneyfication, begun back in the Nineties) are certainly black and white. Others are chromatically indecipherable, I cannot classify them clearly. Some of ‘em form a separate category: those that change colour according to seasons and moments; among these I put, for example, New York and Naples (my city). In some ways, these are the most interesting, because their black and white moments are sort of “coloured”: they have a particular and specific intensity. But here we go into a field that is difficult to walk with words … There are also colourless, neutral cities, greyish inside. But let’s forget about those!

London is undoubtedly a black and white city.

I took this photo recently, from behind the window of the Tate Modern cafeteria on the top floor.

London is a city where it is easy to feel comfortable. Because diversity is the rule: it is total, profound, widespread and, because of this, irrelevant. People manage cultural diversity with great naturalness, as a completely normal element, on which there is no need to linger.

One thing I envy of London is that in almost all museums, admission is completely free (and we are talking about “temples of culture”, such as The National Gallery, British Museum o Natural History Museum …). I find it a sign of civilization and foresight in the policies, from which our country is very, terribly, far away.

And then you can enter the stunning Tate Modern without paying a penny, wandering around the huge rooms and then maybe you go up and sit behind the large window of the cafeteria to rest for a while, watching the Thames flow grey and indolent, and perhaps you take a picture… In black and white, of course.

IL COLORE DELLE CITTA’

Le città sono a colori o bianco e nero. È una condizione che non ha poco a che vedere con i colori reali ma che attiene piuttosto alla loro “anima” o, anche, a quella di chi le osserva. Per mia indole e orientamento estetico, con alcune eccezioni, sono più attratto dalle città in bianco e nero. E non a caso, le foto più nitidamente presenti nella mia memoria sono in bianco e nero.

Bangkok è una città a colori, Rangoon, San Francisco, Città del Messico sono a colori. Invece Berlino, Parigi, Praga (almeno quella precedente alla sua devastante disneyficazione cominciata negli anni ’90) sono senz’altro in bianco e nero. Altre sono cromaticamente più indecifrabili, non riesco a classificarle in modo netto. Alcune costituiscono una categoria a parte: quelle che cambiano colore a seconda delle stagioni e dei momenti ,tra queste metto, per esempio, New York e Napoli (la mia città). Per certi versi, queste sono le più interessanti, perché i loro momenti in bianco e nero sono, in qualche modo, “colorati”. Hanno una particolare e specifica intensità Ma qui ci addentriamo in un campo difficilmente percorribile con le parole… Ci sono anche città incolori, neutre, grigiastre dentro. Ma quelle lasciamole perdere!

Londra è senza dubbio una città in bianco e nero.

Questa foto l’ho scattata recentemente, da dietro la vetrata della caffetteria all’ultimo piano Tate Modern. Londra è una città dove è facile sentirsi a proprio agio. Perché la regola è la diversità, totale, profonda, diffusa e, per tutto questo, irrilevante. La gente gestisce le diversità culturale con grande naturalezza, come elemento del tutto normale, sul quale nemmeno è il caso di soffermarsi.

Una cosa che invidio a Londra è che in quasi tutti i musei l’ingresso è completamente gratuito (e parliamo di templi della cultura” come la National Gallery, il British Museum o il Natural History Museum…). Lo trovo un segno di civiltà e di lungimiranza nelle policy da cui il nostro Paese è molto, terribilmente, lontano.

E quindi si può entrare alla Tate Modern senza pagare un penny, gironzolare per le enormi sale e poi magari salire su, e sedersi dietro la grande vetrata della caffetteria per riposarsi un po’, mentre si guarda il Tamigi scorrere grigio e indolente, e forse scattare una foto. In bianco e nero, ovviamente.

by Cleto Corposanto, exclusive for The diagonales

After all, there are two pressing recommendations related to this phase 2 of the Covid19 pandemic, the one that allows us to leave the houses in which we have been holed up for a couple of months: use of the mask (especially when indoors) and distance. It is not difficult, although many show signs of impatience to follow the rules, but this is another matter. We fly over the mask, which has already become a fashion object as was easily foreseeable. And we stay on the distance, because it is full of interesting implications.

I remember that when I was seven / eight years old, in Bari, South Italy, the city where I was born and lived up to the eighteenth year of age, a game that was played on the street especially in the summer was in vogue among my friends afternoons were long and sunny. Fortunately, they had not yet invented the playstation and therefore all our activities were on the road. So the game, very simple, was to walk behind people who were walking being very careful not to step on their … shadow. Because this involved a pledge to be paid to the group.

This childhood memory came back to me when I visited Japan. A place very far from Italy and not only geographically but above all culturally. In reality, Japan is far from any other culture: the Japanese (who, remember, are islanders, and this takes on importance) are very attached to their traditions, of course, as we all are, but they are a little more. They defend their specificity and typicality while keeping alive a series of traditions and lifestyles that cover many aspects of everyday life, including clothing.I took this photo in Osaka in 2018. I was very intrigued by these two young Japanese girls who were discussing who knows what: they were dressed in traditional clothes (a fairly widespread choice even among the younger generations) and above all they respected one of the cornerstones of culture Japanese, expressible with the term / concept of Hedataru.

Hedataru means to separate, and indicates a situation in which distance is an indicator of demand for one’s own living space, it is the space that surrounds each person, like a sort of “bubble”, described by anthropologist Edward T. Hall in 1963 to indicate the study of proximity relationships in non-verbal communication called proxemics, a term he coined himself. In short, Japanese culture recognizes the physical distance – albeit minimal – of a somewhat salvific meaning, exactly like what we all need today, citizens of the globalized world, to defend ourselves from the danger of infection.

And it struck me, studying the meaning of the value of distance (physical but also social, in its sociological meaning) to discover that Japanese children also play kage fumes (“trampling on each other’s shadow”), which symbolically represents the violation of personal space. In short, the opposite of the game we played in Bari between the 1950s and 1960s.

When it is no longer the time of Hedataru, and therefore when things change and there is no longer any need for separation, we go towards Najimu, a term that expresses entering into confidence (and intimacy) with someone. Then the distances are reset, but safe in a relationship deemed non-dangerous and at zero risk.

Here, Covid19 has suddenly extended the concept of Hedataru to the entire world population, imposing on us that distance that does not make us step on the shadow of others. And it can save our lives, as we slowly seek a return to Najimu which from now on will perhaps no longer be possible as we intended it before. And this too will be a small legacy that will leave us this pandemic time.

In fondo sono due le raccomandazioni pressanti legate a questa fase 2 della pandemia Covid19, quella che ci permette di uscire dalle case nelle quali siamo stati rintanati per un paio di mesi: uso della mascherina (in particolare quando si è al chiuso) e distanza. Non è difficile, anche se molti mostrano segni di insofferenza a seguire le regole, ma questo è un altro discorso. Sorvoliamo sulla mascherina, già diventata oggetto fashion come era facilmente prevedibile. E restiamo sulla distanza, perché ricca di risvolti interessanti. Ricordo che quando avevo sette/otto anni, a Bari, la città dove sono nato e ho vissuto fino al diciottesimo anno d’età, fra i miei amici coetanei era in voga un gioco che si faceva per strada soprattutto d’estate, quando i pomeriggi erano lunghi e assolati. Non avevano ancora inventato la playstation, fortunatamente, e quindi tutte le nostre attività era in strada. Dunque il gioco, semplice semplice, era quello di camminare dietro le persone che passeggiavano stando molto attenti a non calpestare la loro… ombra. Perché questo comportava un pegno da pagare al gruppo.

Mi è tornato in mente questo ricordo dell’infanzia quando ho visitato in Giappone. Un posto molto lontano dall’Italia e non solo geograficamente ma soprattutto culturalmente. In realtà il Giappone è lontano da qualsiasi altra cultura: i giapponesi (che, ricordiamolo, sono isolani, e questa conta) sono molto legati alle loro tradizioni, certo, come lo sono tutti, ma loro un po’ di più. Difendono la loro specificità e la propria tipicità mantenendo vive una serie di tradizioni e di stili di vita che coprono moltissimi aspetti della quotidianità, vestiario incluso.

Ho scattato questa foto a Osaka nel 2018. Mi hanno molto incuriosito queste due giovani ragazze giapponesi che discutevano fra loro chissà di cosa: erano vestite con abiti tradizionali (una scelta abbastanza diffusa anche fra le giovani generazioni) e soprattutto rispettavano uno dei capisaldi della cultura giapponese, esprimibile con il termine/concetto di Hedataru.

Hedataru significa separare, e indica una situazione nella quale la distanza è indicatore di richiesta del proprio spazio vitale, è lo spazio che circonda ogni persona, come una sorta di “bolla”, descritto dall’antropologo Edward T. Hall nel 1963 per indicare lo studio delle relazioni di vicinanza nella comunicazione non verbale parlando di prossemica, termine da lui stesso coniato. La cultura giapponese, insomma, riconosce alla distanza fisica – sia pure minima – un significato in qualche modo salvifico, esattamente come quello di cui oggi abbiamo bisogno tutti, cittadini del mondo globalizzato, per difenderci dal pericolo dell’infezione. E mi ha colpito, studiando il significato del valore della distanza (fisica ma anche sociale, nella sua accezione sociologica) scoprire che anche i bambini giapponesi giocano a kage fumi ( “calpestarsi l’ombra a vicenda”), che rappresenta simbolicamente proprio la violazione dello spazio personale. Insomma, il contrario del gioco che facevamo noi a Bari a cavallo fra gli anni ‘50 e ’60 del secolo scorso.

Quando non è più il tempo dell’Hedataru, e quindi quando le cose cambiano e non c’è più necessità di separazione, si va verso il najimu, termine che esprime l’entrare in confidenza (e in intimità) con qualcuno. Allora le distanze si azzerano, ma al sicuro dentro una relazione giudicata non pericolosa e a rischio nullo.

Ecco, Covid19 ha improvvisamente esteso il concetto di Hedataru all’intera popolazione mondiale, imponendoci quella distanza che non ci fa calpestare l’ombra degli altri. E ci può salvare la vita, mentre cerchiamo lentamente un ritorno al najimu che d’ora in poi non sarà forse più possibile come lo intendevamo prima. E anche questa sarà una piccola eredità che ci lascerà la pandemia.

WHABI-SABI

I don’t like being photographed. Perhaps, for some arcane reason, I inherited the belief that was of various cultures – and in some of them, surprisingly, still exists – that photography is a sort of spell, of magic, through which the soul of the one who’s portrayed in the picture gets stolen. Or, more trivially and likely, I just don’t like my image and I have never been able to accept it completely. But this is a very little interesting speech.

I never knew the person portrayed in the photo, I never talked to him, I don’t know who he is. Yet, in some ways, for thirteen years I have felt him close.

I “stole” this photo (and I swear I also felt guilty about it, I … who don’t want to be pictured). I took it in a modest inn near the Tokyo fish market. It was 7.30 in the morning of a sultry September in 2007. I went out at dawn to browse the huge and fascinating Tsukiji, the fish market (at the time the largest in the world) where 65,000 people worked and where the picturesque tuna auctions were held. Around 7.00 am, most of the negotiations were already over and the market workers poured out, tired and hungry, in the dozens of small restaurants inside and outside Tsukiji. And so did I.

Lost in my steaming misoshiro, I had placed my Nikon on the table. At a certain momet, I noticed him, he was on my right, motionless, with his gaze fixed, flooded by the morning light. His gaze expressed something deep and powerful. Cautiously I turned on the Nikon, without moving it of an inch, and snapped.

Since then this image has accompanied me. Sometimes I don’t watch it for many months but I think about it often. I don’t know if and how much soul there is inside this picture. But for me it represents the soul of Japan, of my Japan, of course.

In Japanese culture the concept of wabi-sabi assumes a great importance. Like all words meaning deeply connoting and specific aspects of a culture, it is practically untranslatable.

Wabi refers to the idea of rustic simplicity but also of sobriety, discretion, silence.

Sabi is the beauty or serenity that accompanies advancing age, when time, with its inexorable “patina”, marks the appearance of things.

And both terms contain a nuance of desolation, of solitude and melancholy but at the same time of sad and imperfect beauty, of poignant and introverted tenderness.

Here I’m… pathetically trying to express in words what every Japanese “knows” and cannot express in words.

This photo, for me, is wabi-sabi. That’s it!

WHABI-SABI

Non amo essere fotografato. Forse, per qualche arcano motivo, ho ereditato quella convinzione che fu di svariate culture – e in alcune di esse ancora, sorprendentemente, permane – che la fotografia costituisca una sorta di sortilegio, di magia, attraverso cui si “ruba l’anima” di chi è ritratto. O, più banalmente e verosimilmente, non mi piace la mia immagine e non sono mai riuscito ad accettarla del tutto. Ma questo è un discorso poco interessante.

La persona ritratta nella foto non l’ho mai conosciuta, non ci ho mai parlato, non so chi sia.

Eppure, per certi versi, da tredici anni la sento vicina.

Questa foto l’ho “rubata” (e mi sono anche sentito in colpa per questo, io… che non voglio essere fotografato). L’ho scattata in una modesta locanda a ridosso del mercato del pesce di Tokyo. Erano le 7.30 di mattina di un afoso giorno di settembre del 2007. Ero uscito all’alba per curiosare nell’abnorme e affascinante Tsukiji, il mercato del pesce (all’epoca il più grande del mondo) dove lavoravano ben 65.000 persone e dove si tenevano le pittoresche aste dei tonni. Intorno alle 7.00, la gran parte delle contrattazioni già finiva e i lavoratori del mercato si riversavano, stanchi e affamati, nelle decine di piccole trattorie dentro e fuori Tsukiji. E così feci anch’io.

Perduto nei mio misoshiro fumante, avevo poggiato la mia Nikon sul tavolo. Mi accorsi ad un certo punto di lui, era sulla mia destra, immobile, con lo sguardo fisso, inondato dalla luce mattutina. Il suo sguardo esprimeva qualcosa di profondo e potente. Cautamente accesi la Nikon senza spostarla di un centimentro, e scattai. Da allora questa immagine mi accompagna. Talvolta non la guardo per molti mesi ma ci penso spesso. Non so se e quanta anima ci sia in questa foto. Ma per me rappresenta l’anima del Giappone, del mio Giappone, ovviamente.

Nella cultura giapponese il concetto di wabi-sabi assume una grande rilevanza. Come tutti le parole che significano aspetti profondamente connotanti e specifici di una cultura, esso è praticamente intraducibile.

Wabi rinvia all’idea di semplicità rustica ma anche di sobrietà, di discrezione, di silenzio.

Sabi è la bellezza o la serenità che accompagnano l’avanzare dell’età, quando il tempo, con la sua “patina” inesorabile, segna l’aspetto delle cose.

Ed entrambi i termini contengono una sfumatura di desolazione, di solitudine, di malinconia ma nel contempo di bellezza triste e imperfetta, di struggente e introversa tenerezza.

Ecco… sto cercando di esprimere pateticamente a parole ciò che ogni giapponese “sa” e non sa esprimere a parole.

Questa foto, per me, è wabi-sabi.

WHAT GAME DO WE PLAY?

One of the things that will perhaps remain in our mind after the CoVid19 pandemic will be a new balance with time. We have re-discovered (someone has perhaps just discovered) that there is not only a mood to live this life of ours; in short, it is not mandatory to live with the paradigm of speed.

The forced lockdown put us in front of a renewed daily life made of slower, more relaxed gestures and gave us back an amount of time that we thought we didn’t have (and that before was in part destined to travel and ended up burnt in the endless queues in the car or in any other means of transport).

We had – and frankly I hope everyone understands it as a strong message – a need that seemed imperative: run, run, run, do things, chasing a goal that seemed to move proportionally to our need to chase it. Chasing a dragonfly on the lawn. Leisure, play too, required continuous pursuits, updates and improvements of the latest generation, with a burning time as if there was no tomorrow. As soon as it is released, something already seems obsolete.

It is curious that in these days when we celebrate the 40th anniversary of Pac-Man, the cult video game born in Japan from a fantastic idea of Toru Iwatani and which conjugated ghosts and a hypothetical pizza that ran not to be bitten, I stopped to relate this photo that I took only less than a year ago in Myanmar, the former Burma.

Last December, in a village not far from the capital Yangon, I immortalized this game room (for us) of the past, a P-2 game station (with the addition of Phone, Mp-3 and Mp-4 on the cartel). A canopy, a few plastic chairs, open air and the desire to tinker typical of the very young.

The irrefutable proof that playing is a form of the mind, that the desire to socialize and have fun transcends the possession of the latest generation of smartphones or video games, and overcomes the barriers of the exaltation of technologies. We are getting used to playing using our imagination and not just the latest, innovative opportunities that technology makes available to us. Perhaps, but I’m not sure, the generalized slowdown that the pandemic has triggered can be a useful brake. To start again with less anxiety and enjoying more of our time available. And to return to play less globalized (in ways, desires and times).

Una delle cose che ci resterà forse in mente dopo la pandemia CoVid19 sarà un ritrovato equilibrio con il tempo. Abbiamo ri-scoperto (qualcuno magari ha proprio scoperto) che non esiste solo un mood per vivere questa nostra vita; che non è insomma obbligatorio convivere con il paradigma della velocità. Il lockdown forzato ci ha messo difronte a una rinnovata quotidianità fatta di gesti più lenti, più rilassati e ci ha restituito una quantità di tempo che pensavamo di non avere (e che prima era destinato a spostamenti e finiva bruciato nelle interminabili code in macchina o in qualsiasi altro mezzo di trasporto). Avevamo – e francamente spero tutti quanti lo recepiscano come un messaggio forte – una necessità che pareva inderogabile: correre, correre, correre, fare cose, inseguendo un traguardo che pareva allontanarsi proporzionalmente al nostro bisogno di rincorrerlo. Inseguendo una libellula sul prato. Anche il leisure, il gioco, necessitavano di continue rincorse, aggiornamenti e migliorie di ultima generazione, con un bruciare tempo come se non ci fosse un domani. Appena uscita, una cosa sembra già obsoleta.

È curioso che proprio in questi giorni che si festeggia il quarantesimo di Pac-Man, il videogioco cult nato in Giappone da un’idea fantastica di Toru Iwatani e che coniugava fantasmini e una ipotetica pizza che correva per non essere azzannata, mi sia soffermato a riguardare questa foto che ho scattato solo meno di un anno fa in Myanmar, la ex Birmania. Lo scorso dicembre, in un villaggio non molto distante dalla capitale Yangon, ho immortalato questa sala giochi (per noi) d’altri tempi, una P-2 game station (con aggiunta di Phone, Mp-3 e Mp-4 in cartello). Una tettoia, qualche sedia di plastica, aria aperta e la voglia di smanettare tipica dei giovanissimi anche li.

La prova inconfutabile che giocare è una forma della mente, che la voglia di socializzare e divertirsi trascende dal possesso dell’ultima generazione di smartphone o videogame, e supera le barriere della esaltazione delle tecnologie. Ci stiamo disabituando a giocare utilizzando la nostra fantasia e non soltanto le ultime, innovative opportunità che la tecnologia ci mette a disposizione. Forse, ma non ne sono sicuro, il rallentamento generalizzato che la pandemia ha innescato può essere un freno utile. Per ripartire con meno angosce e godendo di più del nostro tempo a disposizione. E per tornare a giocare meno globalizzati (nei modi, nei desideri e nei tempi).

THAT GREEN IN COLCHESTER

How many dreams, how much desire to grow …

At the turn of the 70s and 80s, Italian Sociology had elected the University of Colchester as the best place to train its young scholars. It was a period, it is worth remembering, in full reinforcement of a quantitative approach to social facts that, since then, would have made fortunes (and misfortunes) of the discipline. But in short, at Essex Univ you had to go.

I went there too, of course; in Trento I already had a research grant but Essex’s call was formidable.In the meantime, it must be said that a Milan-London was my baptism in the air, in 1978. There was a scheduled flight from Milan Linate to London Gatwick, but it was very expensive. Traveling by plane was still considered a luxury for a few. Fortunately, already there were low cost flights: then, to save money, we went from Trento to Milan by train, then by bus from the Central to Porta Garibaldi Raylway Station because from there the bus that then connected Milan to Malpensa started. Then the flight, with Monarch Airlines, to Luton, train from Luton to Victoria Station, subway to Liverpool Street Station, train to Colchester and finally bus to Campus.

In short, a very big journey. It took the same amount of time that today it takes to go to Bangkok, practically…

And then you were finally there, in the temple. Immersed in a campus that, we who came from universities deeply rooted in the urban reality of our cities, we had never seen. It was there that we all became students (even if the “luckiest” already did exercises and exams in their faculties in Italy), full-time students with the whole day full of courses and seminars and a few hours free. We took this photo probably on a weekend, when lessons were suspended; we spent afternoons on the grass discussing about Sociology and the future, when there was no nostalgia for the sea and then we went to Clacton on the sea …And in the evening it was a sort of cooking festival: in the towers where there were apartments for us students, there was a flourishing of dinners between different groups, in that university spirit that anyone who has been an off-site student knows well. Sometimes it was decided to go out to town for dinner. Colchester was not far from campus, and as the lira / pound exchange rate was not very favorable to us, we often ended up eating at the Chinese economy, where it was better to announce the arrival with a phone call.

At the time of the call Giovanni always came forward, volunteering. He called the Chinese restaurant and announced the arrival of tot people … and when the time came to communicate the name he started with his fast spelling: Ei-en-ei-en-ai-ei. Unforgettable. Giovanni Anania is at the center of the photo, serious gaze and head resting on his fist. A Catanzarese doc who had elected Cosenza to his home of studies. And at Unical he then made his entire academic career, full professor of Agricultural Economics with vast international relationships. We spoke on the phone a few times, especially when I moved to Calabria to teach. Then, five years ago, Giovanni left. Suddenly. The memory of an exquisite, cultured and highly educated person remains alive in me.

QUEL PRATO A COLCHESTER

QUEL PRATO A COLCHESTER

Quanti sogni, quanta voglia di crescere…

A cavallo fra gli anni ’70 e ’80 la sociologia italiana aveva eletto l’Università di Colchester come sede per formare i propri giovani studiosi. Si era, val la pena di ricordarlo, in pieno rafforzamento di un approccio quantitativo ai fatti sociali che, da allora, avrebbe fatto fortune (e sfortune) della disciplina. Ma insomma, a Essex bisognava andarci. Ci sono andato anch’io, naturalmente; a Trento avevo già un assegno di ricerca ma il richiamo di Essex era formidabile. Intanto va detto che proprio un Milano-Londra è stato, nel 1978, il mio battesimo dell’aria. C’era il volo di linea da Milano Linate a Londra Gatwick, ma erano altre cifre.

Viaggiare in aereo era ancora considerato un lusso per pochi. E c’erano per fortuna le low cost già allora: per risparmiare, si andava da Trento a Milano in treno, poi in autobus da centrale a Porta Garibaldi perché da li partiva l’autobus che allora collegava Milano a Malpensa. Poi il volo, con la Monarch Airlines, fino a Luton, treno da Luton a Victoria Station, metro fino a Liverpool Street Station, treno per Colchester e infine autobus per il campus. Un viaggione, insomma. Ci si metteva lo stesso tempo che oggi ci si impiega per andare a Bangkok, praticamente…

E poi finalmente eri li, nel tempio. Immersi in un campus che, noi che venivamo da Università profondamente radicate nei tessuti urbani delle nostre città, non avevamo mai visto. Era li che tutti noi tornavamo studenti (anche se i più “fortunati” facevano già esercitazioni ed esami nelle proprie Facoltà in Italia, e qualcuno era addirittura già incaricato), studenti a tempo pieno con tutta la giornata piena di corsi e seminari e poche ore libere. Questa foto l’abbiamo scattata probabilmente in un weekend, quando le lezioni erano sospese; passavamo pomeriggi sull’erba a discutere di sociologia e futuro, quando non ci veniva la nostalgia del mare e allora facevamo un salto a Clacton on the sea …

E la sera era un festival della cucina: nelle torri dove c’erano gli appartamenti per noi studenti, era tutto un fiorire di cene fra gruppi diversi, in quello spirito universitario che chiunque sia stato un fuori sede conosce bene. Qualche volta si decideva di andare a cena fuori, in città. Colchester era non molto distante dal campus, e siccome il cambio lira/sterlina non era a noi molto favorevole, spesso finivamo per mangiare all’economico cinese, dove comunque era meglio preannunciare l’arrivo con una telefonata.

Al momento della telefonata si faceva avanti sempre Giovanni, offrendosi volontario. Chiamava il ristorante cinese e preannunciava l’arrivo di tot persone… e quando arrivava il momento di comunicare il nome partiva con il suo velocissimo spelling: Ei-en-ei-en-ai-ei. Indimenticabile. Giovanni Anania è al centro della foto, sguardo serio e testa appoggiata al pugno. Un catanzarese doc che aveva eletto Cosenza a propria sede di studi. E all’Unical ha poi fatto tutta la sua carriera accademica, da professore ordinario di Economia agraria con vastissimi rapporti internazionali. Ci siamo risentiti al telefono un paio di volte, specialmente quando a mia volta ho scelto la Calabria per insegnare. Poi, cinque anni fa, Giovanni se n’è andato. All’improvviso. Resta vivo, in me, il ricordo di una persona squisita, colta e di grande cultura.